Volume 11, Issue 3 (2025)

Pharm Biomed Res 2025, 11(3): 201-214 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Osarieme Imade R, Ayinde B A, Iyawe A O, Ogbemudia C O. Antifibroid and High-performance Liquid Chromatography Analysis of Azadirachta indica (Meliaceae) Leaves. Pharm Biomed Res 2025; 11 (3) :201-214

URL: http://pbr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-680-en.html

URL: http://pbr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-680-en.html

Rose Osarieme Imade *1

, Buniyamin Adesina Ayinde1

, Buniyamin Adesina Ayinde1

, Andrex Osatohanmwen Iyawe1

, Andrex Osatohanmwen Iyawe1

, Charles Osemwegie Ogbemudia1

, Charles Osemwegie Ogbemudia1

, Buniyamin Adesina Ayinde1

, Buniyamin Adesina Ayinde1

, Andrex Osatohanmwen Iyawe1

, Andrex Osatohanmwen Iyawe1

, Charles Osemwegie Ogbemudia1

, Charles Osemwegie Ogbemudia1

1- Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin, Nigeria.

Keywords: Azadirachta indica, Fibroid, High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Histology, Hormones

Full-Text [PDF 2401 kb]

(173 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (606 Views)

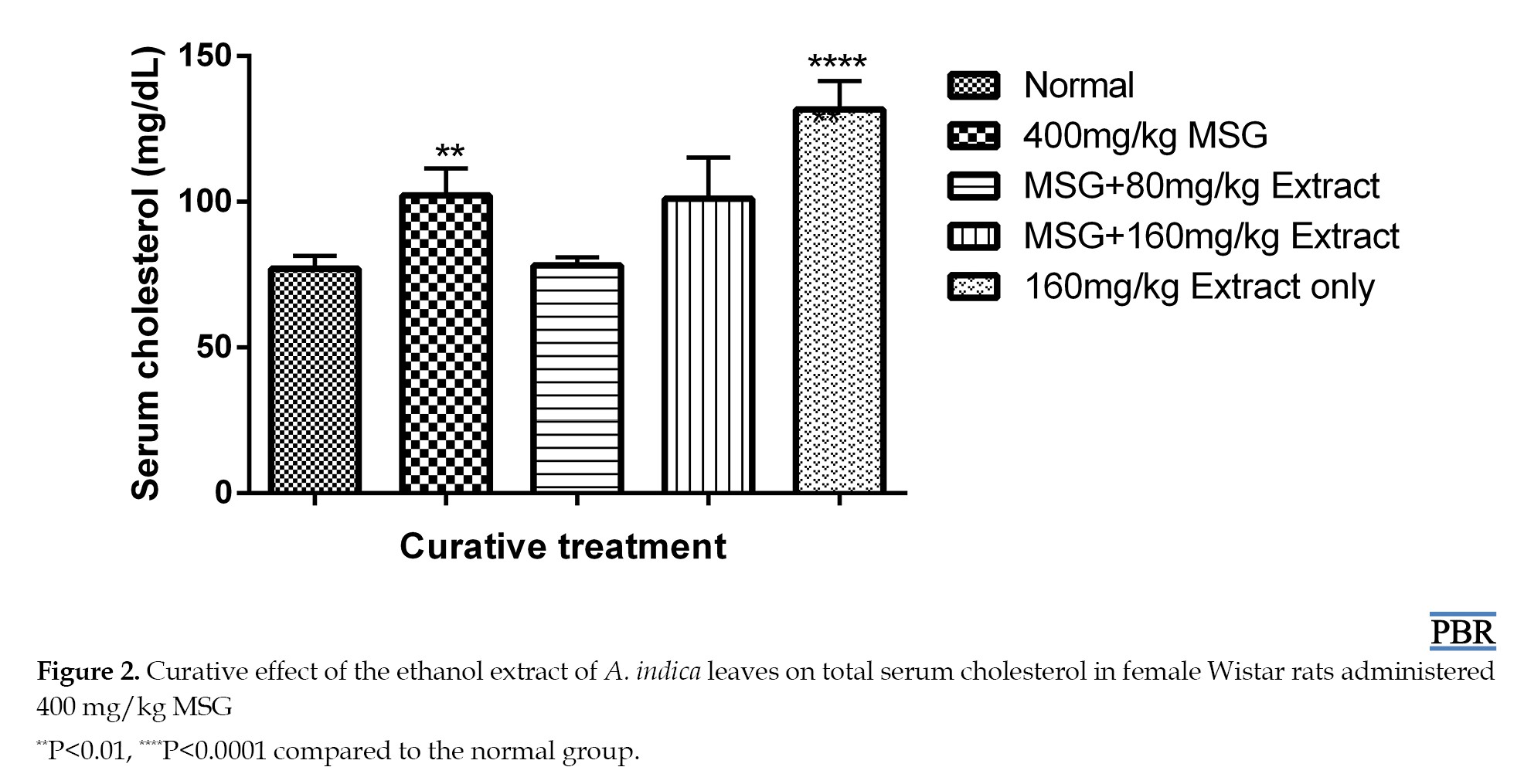

Total protein content

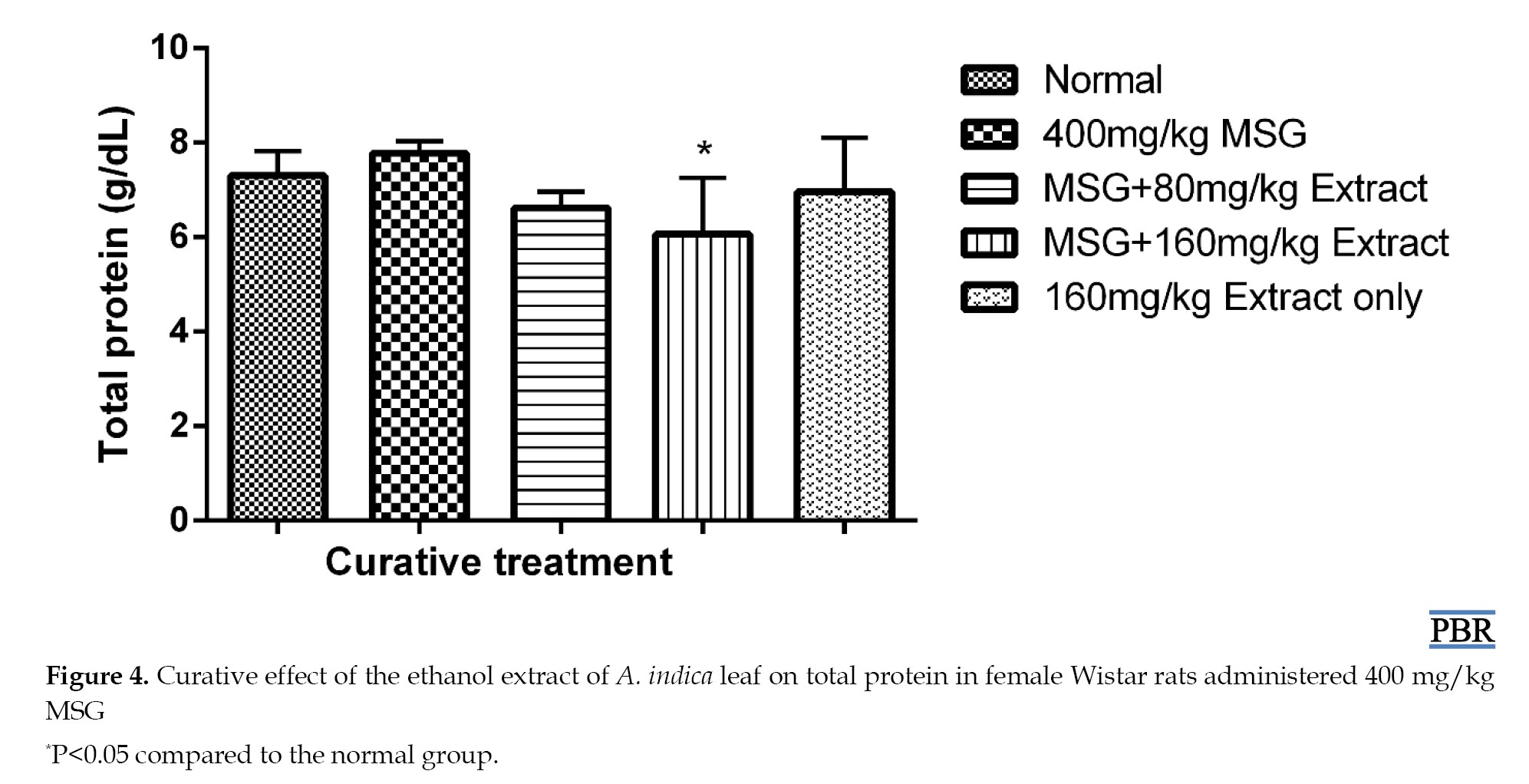

No significant increase (P≥0.05) was observed in total plasma protein levels in normal female Wistar rats treated with 400 mg/kg MSG, both in the preventive and curative treatments (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

The acute toxicity test results indicated that oral administration of A. indica leaf extract induced mortality in mice only at 5000 mg/kg, indicating that the plant extract is relatively safe at lower doses. No sedation, diarrhoea, change in gait, or body posture was observed at lower doses in the mice, and no decreased locomotory activity or hyperactivity was observed.

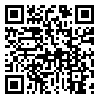

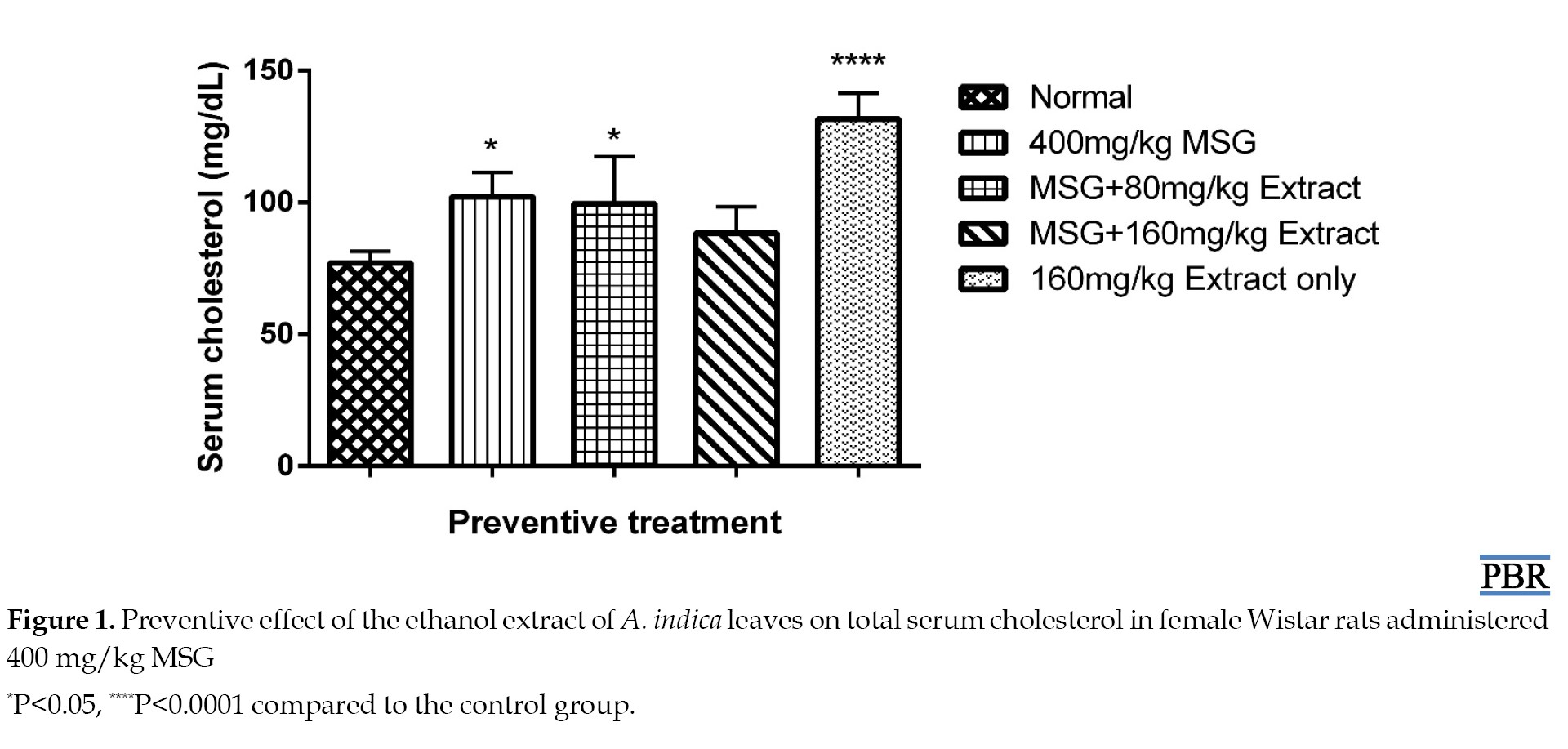

There was a considerable increase in cholesterol following the administration of MSG in both the curative and preventive tests. The extract demonstrated better ability to lower increased cholesterol levels in the curative experiment than in the preventive. The ability of the leaf extract to lower cholesterol may be due to a decrease in dephosphorylated 3-hydroxyl-3-methoxylglutamyl-CoA reductase (HMGR) levels, as well as an adverse effect on cholesterol production caused by the activation of glucagon and adrenaline [18]. Cholesterol is a crucial building block for the formation of many steroid hormones, which are powerful signaling molecules that control several processes in the body Elevatied serum cholesterol levels are typically linked to the activation of the enzyme HMGR, which catalyzes the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, the rate-limiting step of cholesterol synthesis [19].

The formation and development of uterine fibroids have been linked to ovarian steroid hormones, which have been shown to be crucial molecular indicators. Estradiol is unique in its ability to promote the growth of uterine cells because it binds to ERα receptors in the uterus and forms a complex that interacts with DNA in the nucleus to activate transcriptional promoters and enhancer regions that govern gene expression. This allows ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase II binding and the subsequent start of transcription, leading to protein production and increased uterine and ovarian cell proliferation [20].

Certain proteins linked to uterine fibroids have been shown to rise in response to MSG. This results from activating RNA polymerase and increasing its activity, activating transcriptional enhancer and promoter regions that control the production of genes linked to protein development [14]. In this study, there was no discernible difference between the MSG and treatment groups’ total protein content compared with the normal group. This is comparable to the results of previous studies [21].

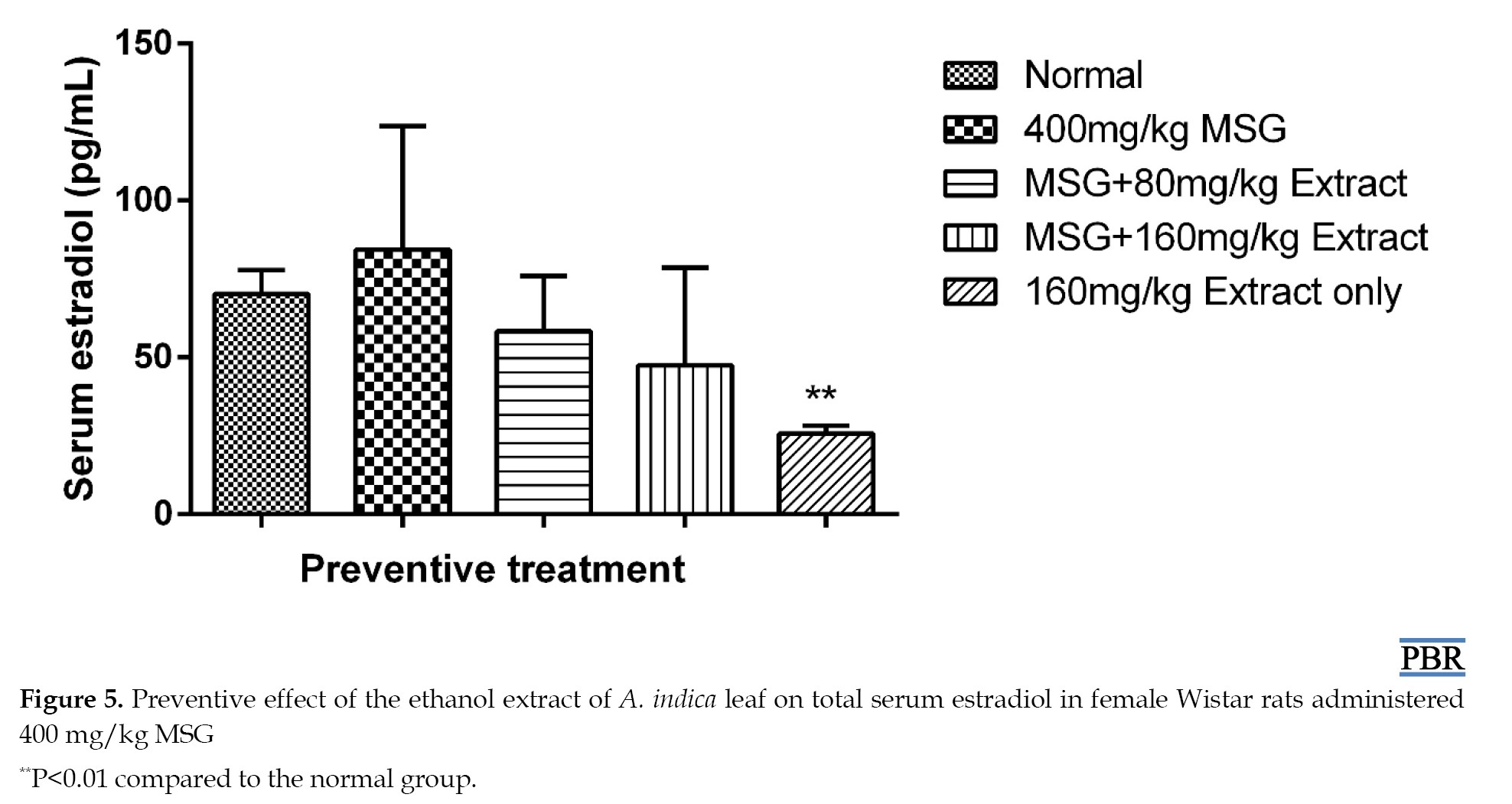

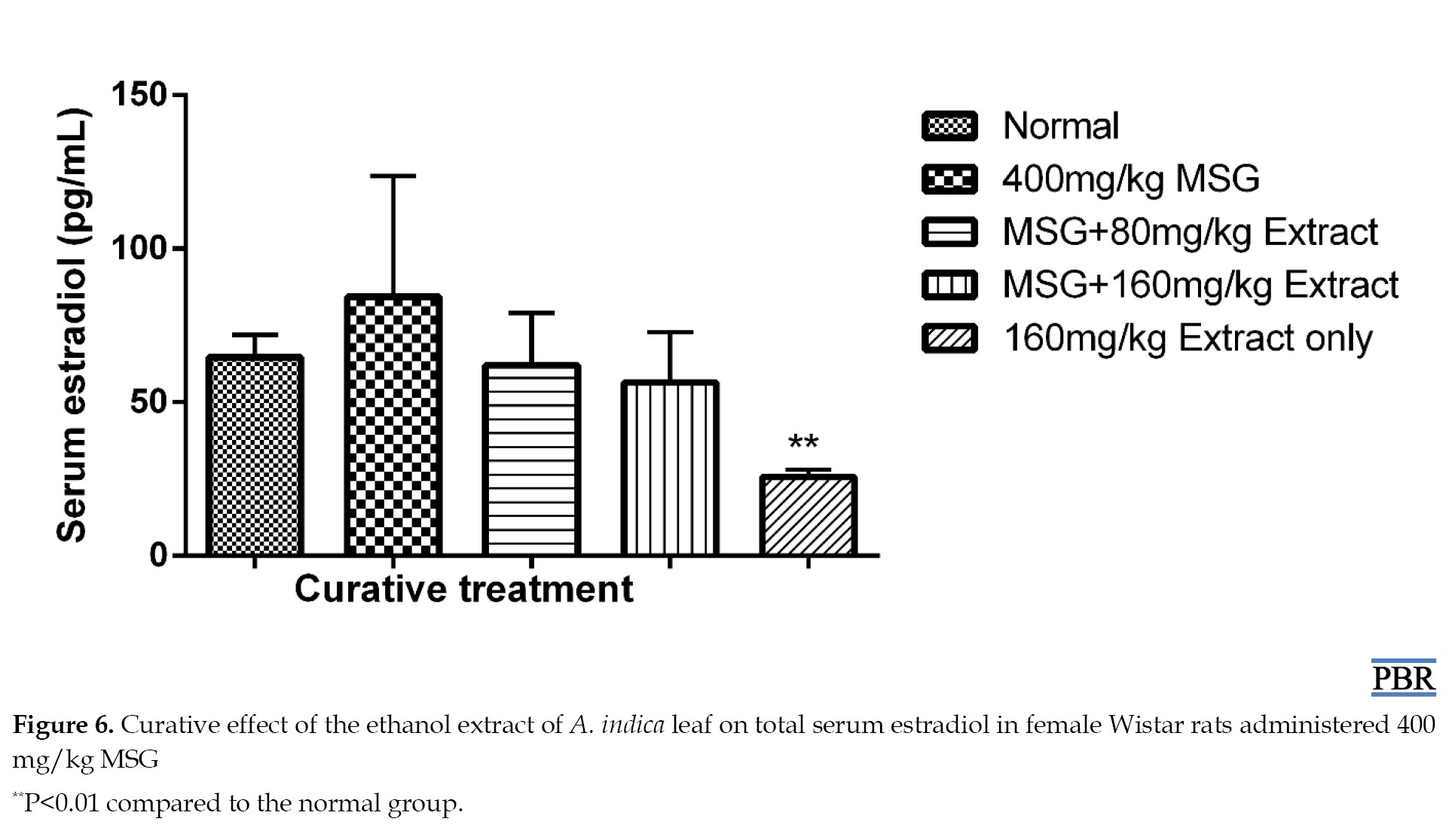

In both curative and preventive trials, treatment with the ethanol extract of A. indica leaves lowered the increased estradiol levels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). Its effect on estradiol may be due to the inhibition of the enzyme aromatase, which is responsible for aromatizing testosterone and androstenedione to estrogens during the production of estradiol from cholesterol [15]. It may also contain phytochemicals that function as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, which, when stimulated continuously decrease, the expression or downregulate GnRH receptors on the anterior pituitary. Alternatively, it may be caused by an inducer of liver microsomal enzyme that increases estradiol metabolism [3]. As a result, less estradiol is generated.

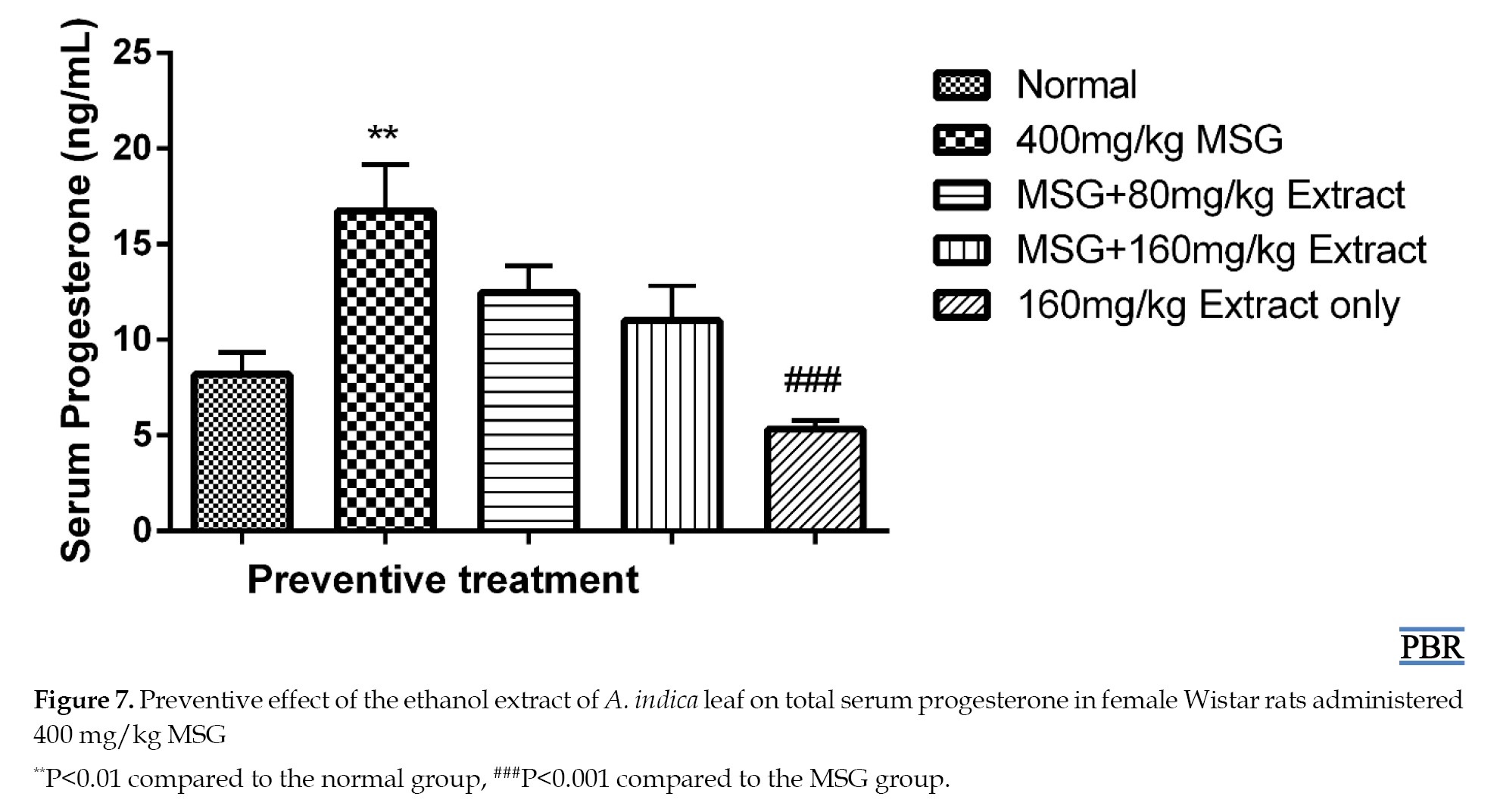

Fibroids are caused by elevated protein, cholesterol, estrogen, and progesterone [3]. Experimental, clinical, and epidemiological data support the idea that ovarian steroid hormones play a role in the pathophysiology of uterine fibroids [22]. The higher progesterone levels were reduced dose-dependent after preventative treatment with A. indica leaf extract. Progesterone primarily affects fibroids via interacting with progesterone receptors, which are expressed more in leiomyomas than in normal myometrium [23]. Many studies have demonstrated that progesterone may play a significant role in interacting with growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins, even if the precise underlying processes that drive extracellular matrix deposition in uterine fibroids are still being investigated [24]. Progesterone has been demonstrated to be the primary mediator of the increase in transforming growth factor-β expression, which is one of the main growth agents that causes uterine fibroids to undergo fibrosis [25].

Saponins, steroids, terpenes, tannins, glycosides, alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, and oxalic acid are among the phytochemicals found in the plant [8]. The presence of these phytochemicals may explain the therapeutic efficacy. Activating the immune system and lowering cholesterol levels are saponins’ health advantages. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that saponin inhibits the aromatase enzyme [8], which is involved in estrogen synthesis. Studies have indicated that the plant has anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties that could be useful in treating fibroid [9]. These anti-proliferative properties may be linked to the presence of limonoids, which can limit cell growth and division. The anti-inflammatory qualities may alleviate the pain and inflammation associated with leiomyoma. Additionally, the antioxidant properties may protect against oxidative stress, which can lead to leiomyoma formation [26].

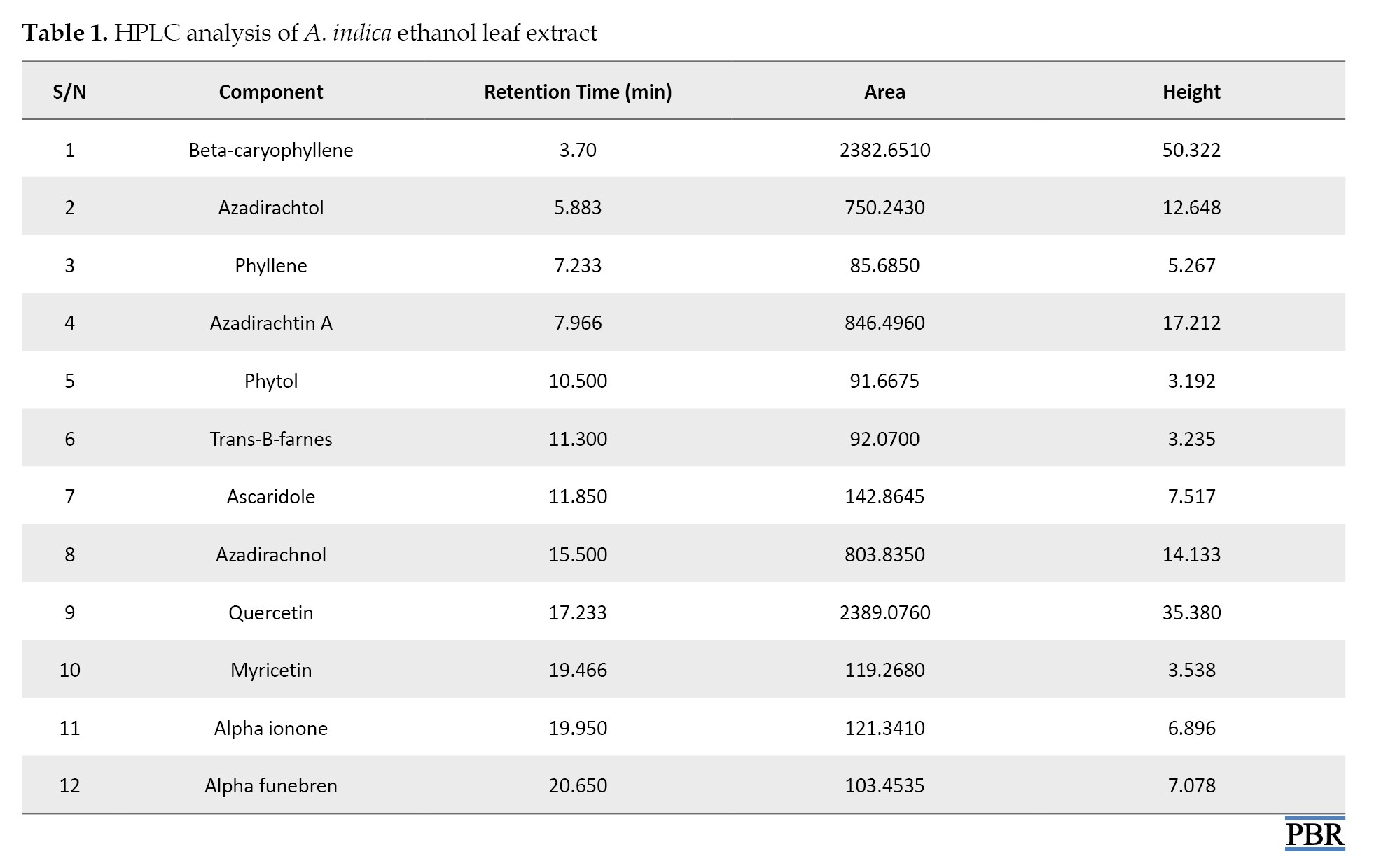

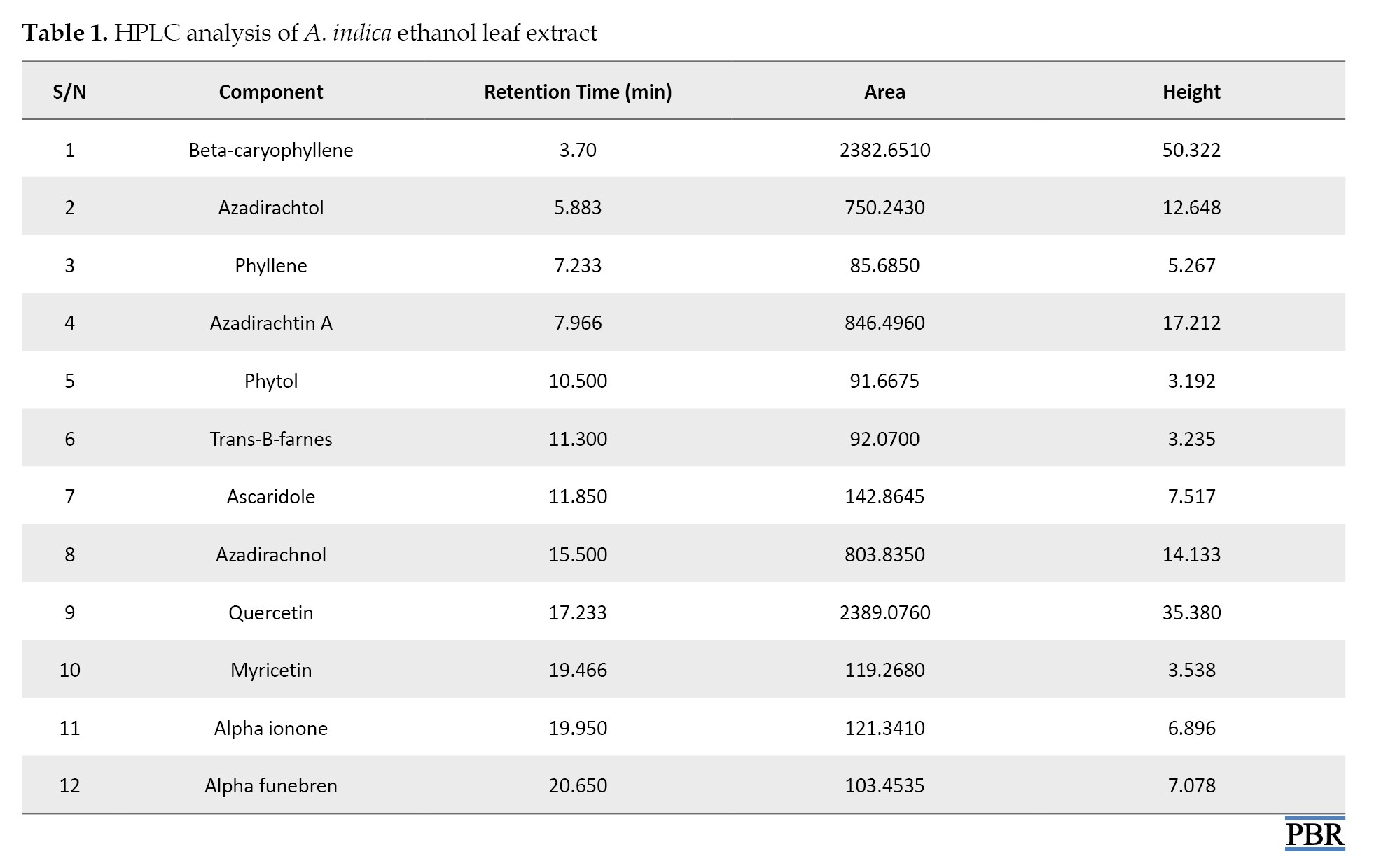

According to the HPLC analysis, the main compounds in the leaf extract of A. indica are beta-caryophyllene, azadirachtol, azadirachtin, azadirachnol, and quercetin (Table 1). These chemicals are implicated in the plant’s numerous medicinal advantages and could help manage uterine fibroids. It has been discovered that beta-caryophyllene is a sesquiterpene that is extensively found in the essential oils of many plants. Beta-caryophyllene is believed to contribute to numerous biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticarcinogenic properties [27]. Azadirachtin has antibacterial and antitumor properties, as well as the ability to reduce edema and encourage tissue healing [9]. Numerous investigations have demonstrated quercetin’s ability to have anticancer effects via various pathways, which have been validated in several in vitro and in vivo tumor models [27].

Conclusion

The levels of cholesterol, progesterone, and estradiol were lowered by the action of A. Indica leaves extract to varying degrees. Reduction of spindle-shaped fibers indicative of fibroid formation was seen at the lower dose of the extract. These results demonstrate the potential of the plant in managing fibroid.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin, Nigeria, authorized all protocols for utilizing animals in the experiment (Code: (EC/FP/023/04).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Rose Osarieme Imade and Buniyamin Adesina Ayinde; Experiments: Iyawe Osatohanmwen Andrex; Project administration: Charles Osemwegie Ogbemudia and Rose Osarieme Imade; Statistical analysis, investigation and writing: Rose Osarieme Imade; Review, editing, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Obasuyi and Queen Okoro of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital in Benin City for their contributions to the preparation of the histology slides and the analysis of the serum biochemical data. Gerald Eze of the Anatomy Department is also greatly appreciated for his help interpreting the histology slides.

Full-Text: (111 Views)

Introduction

Fibroids, sometimes referred to as leiomyoma or myoma, are noncancerous muscle tumors that develop in the uterus. They can range in size from an apple seed to a grapefruit; in certain situations, they can become extremely large. Premenopausal women frequently experience these alterations, and they may revert following menopause [1]. Approximately 30% of the 70% of women who are affected experience symptoms. For women who are still capable of becoming pregnant, it is the most common reason for hysterectomy. Uterine smooth muscle cells give rise to these benign tumors. They are categorized according to their various sites and can develop inside and outside the uterus, impacting the walls or cavity [2].

The precise cause of fibroids remains unknown, despite their prevalence. Although there is still much to learn about the molecular mechanisms underlying their genesis, growth, and regression, researchers have proposed that a variety of factors may be involved. Several channels and mechanisms have been discovered several, including growth factors, sex hormones, stem cells, and epigenetic variables. In particular, estrogen and progesterone significantly impact the pathophysiology of uterine fibroids [3]. Increased protein and cholesterol levels have also been implicated in fibroid formation. Other factors, such as ethnicity, alterations in the extracellular matrix, inflammation, genetic mutations, and exposure to particulate matter, can result in fibroids. They often enlarge during periods of elevated hormone levels and contract when anti-hormonal drugs are taken or after menopause [4]. Symptomatic women usually have iron deficiency anemia, low back pain, abdominal/pelvic pain, and constipation due to heavy or protracted menstruation [1].

No specific treatment plan works for all women because each situation is unique. The size and location of the fibroids, the frequency of fibroid symptoms, the patient’s age and proximity to menopause, and the desire for future pregnancy are some of the criteria that clinicians examine when making treatment decisions. Medication, surgery, and cautious waiting are the current treatments for uterine fibroids, each with disadvantages and potential side effects [4]. Women are increasingly using herbal therapies to treat uterine fibroids because of the potential side effects, high costs, and lack of access to conventional therapies [5].

A Ghanaian herbal mixture called Femitol, composed of Anthocleista nobilis, Vernonia amygdalina, Alstonia boonei, Persea americana, Heliotropium indicum, and Angelica sinensis, succeeded in lowering high cholesterol and estrogen levels and uterine enlargement induced by monosodium glutamate (MSG) [6]. Tissue analyses in another study revealed that an ethanol extract from Diodia sarmentosa leaves prevented leiomyoma and assisted in reversing the metabolic alterations induced by MSG [7].

Neem, or Azadirachta indica, has been used for millennia in traditional medicine due to its numerous therapeutic advantages [8, 9]. Despite anecdotal claims of its use in this area [10], there is a dearth of scientific evidence supporting the plant’s effectiveness in treating fibroids. Therefore, by examining its protective effect on biochemical indicators, such as total cholesterol, protein, progesterone, and estradiol, this study aimed to ascertain its antifibroid action on MSG-induced uterine leiomyoma in Wistar rats. This will be further verified by examining the rats’ uterus histopathologically. The main components of the extract will be identified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

All reagents employed in this study were analytical grade and obtained from established local vendors.

Plant collection and preparation

In December 2023, leaves of A. indica were collected from the University of Benin in Edo State, Nigeria. A voucher specimen bearing the Herbarium number UBH-A286 was deposited at the institute after Akinnibosun Henry confirmed the identity of the leaves. The leaves were completely air-dried and milled into coarse powder, which was extracted with absolute ethanol (99%) using a Soxhlet apparatus at 60 °C. The obtained plant extract was concentrated using a thermo-regulated water bath. The semi-solid plant extract obtained was weighed and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until needed.

Animal handling conditions

The study used adult female non-pregnant Wistar rats weighing between 110 g and 200 g. The rats were obtained from the University of Benin’s Pharmacology department’s animal house and kept in separate, clean plastic cages with wood shavings as bedding, under hygienic and well-ventilated conditions. Animals were provided with clean water and normal pelletized animal food (Chukun Feed, Ibadan). The animals were given two weeks to acclimate. The National Institutes of Health’s established requirements for the humane treatment and care of laboratory animals were followed in this study. Every experimental procedure was performed in compliance with the recommendations and guidelines for the use of animals authorized by the University of Benin’s Faculty of Pharmacy’s Ethical Committee.

Acute toxicity test

Lorke’s approach was used to determine this [11]. Nine mice were divided into three groups of three mice each during phase 1. A. indica leaf extract was administered to each mouse group in varying doses (10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 1000 mg/kg). The animals were kept under observation for a whole day to track their mortality and behavior. Three mice were used in phase two and split into three groups of one mouse each. After receiving larger dosages of A. indica leaf extract (1600 mg/kg, 2900 mg/kg, and 5000 mg/kg), the mice were monitored for unusual behavior and death for a whole day.

Antifibroid effect of A. indica leaves extract

Preventive study

This study was conducted according to the methods described in the literature [7]. Female Wistar rats were divided into five groups, each containing five rats. The drug was administered orally once a day. Group A (control) was the untreated group and was given only distilled water. Group B was treated with 400 mg/kg MSG only. Groups C and D were simultaneously treated with 400 mg/kg MSG and A. indica extract (80, 160 mg/kg). Group E received 160 mg/kg extract only. These doses were chosen based on other studies [12] that documented their subacute safety profiles. All treatments were performed simultaneously over 30 days. On day 31, animals were sacrificed by anesthesia in a chloroform-saturated chamber, and blood was collected by cardiac puncture and transferred to plain bottles which was used for measurements of total plasma cholesterol, protein, progesterone and estradiol. The uterus was surgically removed and transferred to a sterile tissue bottle containing 10% neutral buffered formal saline solution for histopathological examination.

Curative study

The rats were divided into five groups (A, B, C, D, and E), each containing five rats. Group A (control) received only food and water. In an effort to stimulate the uterine fibroid formation, group B was administered 400 mg/kg of MSG for 30 days and thereafter stopped, with normal rat chow continued for another 30 days. Groups C and D were also administered 400 mg/kg of MSG for 30 days to induce fibroids. From the 31st day, groups C and D were administered 80 and 160 mg/kg of A. indica leaf extract, respectively, once daily for another 30 days. Group E was administered 160 mg/kg A. indica leaf extract only for 30 days, after which it was stopped, and food and water were continued for another 30 days. All administrations were performed using means of oral gavage. On the 61st day, the animals were sacrificed, blood samples were collected for biochemical analysis, and the uterus excised for assessment [13].

Biochemical assays

Determination of total cholesterol content

This assay used a semi-automated chemistry analyzer (Mindray BA-88A Reagent system) with an AGAPPE test kit. Following the test kit’s instructions, the analyzer was programmed for the total cholesterol test. The blank microtube received only the cholesterol Biuret reagent (1000 μL). The standard tube was prepared by adding 10 μL of standard cholesterol solution and 1000 μL of the reagent, which was mixed. Sample tubes were prepared by adding 10 μL of sample A1 and 1000 μL of cholesterol reagent, which was also properly mixed in a tube labeled ‘A1’. The same procedure was followed for the remaining samples (A1-E5) in their respective tubes. All tubes were incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C. After incubation, the blank solution was aspirated into the flow cell to establish a baseline measurement in the analyzer. The standard solution and each sample were then measured to determine their absorbance, which was recorded [14].

Determination of total protein content

This assay used a semi-automated chemistry analyzer (Mindray BA-88A Reagent system) and the AGAPPE test kit. Following the test kit’s instructions, the analyzer was programmed for the total protein test. The blank microtube received only the protein Biuret reagent (1000 μL). The standard tube was prepared by adding 20 μL of standard total protein solution and 1000 μL of the reagent, which was properly mixed. Sample tubes were prepared by adding 20 μL of sample A1 and 1000 μL of total protein reagent which was also properly mixed. The same procedure was performed for the remaining samples (A1-E5) in their respective tubes. All tubes were incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C. After incubation, the blank solution was first aspirated into the flow cell to establish a baseline measurement in the analyzer. Then, the standard solution and each sample were measured individually to determine their absorbance, which was recorded for further analysis [6].

Determination of estradiol content

This assay used a microplate reader (Mindray MR-96A), microplate washer (Mindray MW-12A) and E2 Accubind “enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay” (ELISA) kit. Microplate wells for each sample, control, and reference material to compare were set up. A total of 25 μL of each sample was placed in the designated well. Fifty μL of estradiol biotin reagent was added to each well on the test plate. The plates were then gently swirled for 30 seconds and then incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Next, 50 μL of estradiol enzyme reagent was added to all wells. The plate was then incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature. The contents of the plates were discarded, and the plates were dried with absorbent paper. The wells were washed thoroughly with 350 μL wash buffer solution and decanted thrice. Substrate solution (100 μL) was added to each well and incubated for 20 minutes, followed by a 50 μL of stop solution to halt the reaction. The light absorbed by the wells at 450 nm was measured within 15 minutes. Estradiol in the samples was determined using a dose-response curve [15].

Determination of progesterone content

Before proceeding with the assay, all reagents, serum reference calibrators, and controls were brought to room temperature (20-27 °C). Microplate wells were formatted for each calibrator, control, and specimen. The assay was performed in duplicate. A total of 0.025 mL of the appropriate serum reference calibrator, control, and specimen were pipetted into the assigned well. Then 0.05 mL of progesterone enzyme reagent was added to all wells. The microplate was swirled gently for 10-20 seconds to mix. 0.05 mL of progesterone biotin reagent was then added to all wells. The microplate was gently swirled for 10-20 seconds. The mixure was then covered and incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature. The content of the microplate was discarded by decantation, and the plate was also blotted dry with absorbent paper. A total of 0.35 mL of wash buffer was added to the plate. The plate was then decanted and the process repeated two additional times. Substrate reagent (0.1 mL) was then added to all wells, and care was taken not to shake the plate after the addition of the substrate. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes, after which 0.05 mL of stop solution was added to each well and gently mixed for 15-20 seconds. The absorbance was read for each well at 450 nm [15].

Histopathology analysis of organs

A 10% neutral buffered formalin solution was used to fix the tissue. The uterus was placed in appropriately labeled cassettes after being further dissected to choose the best area for inspection. Dehydration was performed using alcohol in an ascending sequence. Xylene was used for clearing, followed by paraffin wax infiltration. Tissues soaked in paraffin wax were then cut into ultra-thin sections of 5 microns using a semi-automated rotary microtome, allowed to dry overnight, and then, after being hydrated, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Dehydration with alcohol was repeated in ascending sequence. The sections were examined under a microscope and photographed after staining with dibutyl phthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX) [16].

HPLC procedure

HPLC analysis was performed at Bato Chemical Laboratory at the Lagos, Nigeria. The HPLC model was Shimadzu (Nexera MX). A special column called a C18 reverse phase column (ubondapak) was used for the separation, with dimensions of length: 100 mm, internal diameter: 4.6 mm, and thickness: 7 μm. A mixture of water and acetonitrile (70% acetonitrile, and 30% water) was used as the mobile phase to move the sample through the column. The HPLC device was connected to a ultraviolet (UV)–Vis diode array detector that uses ultraviolet (UV) light to analyze the chemicals (set at a specific wavelength of 254 nm). A pressure of 15 MPa was applied to push the samples through the column. First, standard solutions were injected into the machine. This resulted in a chromatogram showing peaks that represented the separated chemicals. Then 5 μL of the desired extract was injected into the HPLC system at a 2 mL/min constant flow rate. The device then produced another chromatogram with peaks for the chemicals in the extract. By comparing these peaks to the window set up earlier, the chemicals of interest present in the extract were identified [17].

Data analysis

GraphPad Prism software for Window, version 6.01 was used to create bar graphs showing the data. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze the data, followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the study.

Results

Acute toxicity test

During phase 1 acute toxicity test, no toxicity or mortality was observed at 10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 1000 mg/kg doses (Table 1).

In phase 2 testing, convincing evidence of toxicity and mortality was observed at 5000 mg/kg but no toxicity was observed at 1600 mg/kg and 2900 mg/kg, and no other signs of toxicity were observed; no secretions from the eyes, ear, nose, anus, or external genitalia, as well as no wasting, audible chattering, alopecia, or pallor in the eyes. The rats were not sluggish; they ate well and defecated normally. No ocular abnormalities, decreased motor activity, or neurological problems were observed.

Total serum cholesterol

The treatment of normal female rats with 400 mg/kg MSG resulted in a significant increase (32.73% [P≤0.05]) in plasma cholesterol levels in the preventive treatment. 80 and 160 mg/kg doses of the extract with MSG gave 29.35% and 14.81% increase, respectively (Figure 1).

Fibroids, sometimes referred to as leiomyoma or myoma, are noncancerous muscle tumors that develop in the uterus. They can range in size from an apple seed to a grapefruit; in certain situations, they can become extremely large. Premenopausal women frequently experience these alterations, and they may revert following menopause [1]. Approximately 30% of the 70% of women who are affected experience symptoms. For women who are still capable of becoming pregnant, it is the most common reason for hysterectomy. Uterine smooth muscle cells give rise to these benign tumors. They are categorized according to their various sites and can develop inside and outside the uterus, impacting the walls or cavity [2].

The precise cause of fibroids remains unknown, despite their prevalence. Although there is still much to learn about the molecular mechanisms underlying their genesis, growth, and regression, researchers have proposed that a variety of factors may be involved. Several channels and mechanisms have been discovered several, including growth factors, sex hormones, stem cells, and epigenetic variables. In particular, estrogen and progesterone significantly impact the pathophysiology of uterine fibroids [3]. Increased protein and cholesterol levels have also been implicated in fibroid formation. Other factors, such as ethnicity, alterations in the extracellular matrix, inflammation, genetic mutations, and exposure to particulate matter, can result in fibroids. They often enlarge during periods of elevated hormone levels and contract when anti-hormonal drugs are taken or after menopause [4]. Symptomatic women usually have iron deficiency anemia, low back pain, abdominal/pelvic pain, and constipation due to heavy or protracted menstruation [1].

No specific treatment plan works for all women because each situation is unique. The size and location of the fibroids, the frequency of fibroid symptoms, the patient’s age and proximity to menopause, and the desire for future pregnancy are some of the criteria that clinicians examine when making treatment decisions. Medication, surgery, and cautious waiting are the current treatments for uterine fibroids, each with disadvantages and potential side effects [4]. Women are increasingly using herbal therapies to treat uterine fibroids because of the potential side effects, high costs, and lack of access to conventional therapies [5].

A Ghanaian herbal mixture called Femitol, composed of Anthocleista nobilis, Vernonia amygdalina, Alstonia boonei, Persea americana, Heliotropium indicum, and Angelica sinensis, succeeded in lowering high cholesterol and estrogen levels and uterine enlargement induced by monosodium glutamate (MSG) [6]. Tissue analyses in another study revealed that an ethanol extract from Diodia sarmentosa leaves prevented leiomyoma and assisted in reversing the metabolic alterations induced by MSG [7].

Neem, or Azadirachta indica, has been used for millennia in traditional medicine due to its numerous therapeutic advantages [8, 9]. Despite anecdotal claims of its use in this area [10], there is a dearth of scientific evidence supporting the plant’s effectiveness in treating fibroids. Therefore, by examining its protective effect on biochemical indicators, such as total cholesterol, protein, progesterone, and estradiol, this study aimed to ascertain its antifibroid action on MSG-induced uterine leiomyoma in Wistar rats. This will be further verified by examining the rats’ uterus histopathologically. The main components of the extract will be identified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

All reagents employed in this study were analytical grade and obtained from established local vendors.

Plant collection and preparation

In December 2023, leaves of A. indica were collected from the University of Benin in Edo State, Nigeria. A voucher specimen bearing the Herbarium number UBH-A286 was deposited at the institute after Akinnibosun Henry confirmed the identity of the leaves. The leaves were completely air-dried and milled into coarse powder, which was extracted with absolute ethanol (99%) using a Soxhlet apparatus at 60 °C. The obtained plant extract was concentrated using a thermo-regulated water bath. The semi-solid plant extract obtained was weighed and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until needed.

Animal handling conditions

The study used adult female non-pregnant Wistar rats weighing between 110 g and 200 g. The rats were obtained from the University of Benin’s Pharmacology department’s animal house and kept in separate, clean plastic cages with wood shavings as bedding, under hygienic and well-ventilated conditions. Animals were provided with clean water and normal pelletized animal food (Chukun Feed, Ibadan). The animals were given two weeks to acclimate. The National Institutes of Health’s established requirements for the humane treatment and care of laboratory animals were followed in this study. Every experimental procedure was performed in compliance with the recommendations and guidelines for the use of animals authorized by the University of Benin’s Faculty of Pharmacy’s Ethical Committee.

Acute toxicity test

Lorke’s approach was used to determine this [11]. Nine mice were divided into three groups of three mice each during phase 1. A. indica leaf extract was administered to each mouse group in varying doses (10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 1000 mg/kg). The animals were kept under observation for a whole day to track their mortality and behavior. Three mice were used in phase two and split into three groups of one mouse each. After receiving larger dosages of A. indica leaf extract (1600 mg/kg, 2900 mg/kg, and 5000 mg/kg), the mice were monitored for unusual behavior and death for a whole day.

Antifibroid effect of A. indica leaves extract

Preventive study

This study was conducted according to the methods described in the literature [7]. Female Wistar rats were divided into five groups, each containing five rats. The drug was administered orally once a day. Group A (control) was the untreated group and was given only distilled water. Group B was treated with 400 mg/kg MSG only. Groups C and D were simultaneously treated with 400 mg/kg MSG and A. indica extract (80, 160 mg/kg). Group E received 160 mg/kg extract only. These doses were chosen based on other studies [12] that documented their subacute safety profiles. All treatments were performed simultaneously over 30 days. On day 31, animals were sacrificed by anesthesia in a chloroform-saturated chamber, and blood was collected by cardiac puncture and transferred to plain bottles which was used for measurements of total plasma cholesterol, protein, progesterone and estradiol. The uterus was surgically removed and transferred to a sterile tissue bottle containing 10% neutral buffered formal saline solution for histopathological examination.

Curative study

The rats were divided into five groups (A, B, C, D, and E), each containing five rats. Group A (control) received only food and water. In an effort to stimulate the uterine fibroid formation, group B was administered 400 mg/kg of MSG for 30 days and thereafter stopped, with normal rat chow continued for another 30 days. Groups C and D were also administered 400 mg/kg of MSG for 30 days to induce fibroids. From the 31st day, groups C and D were administered 80 and 160 mg/kg of A. indica leaf extract, respectively, once daily for another 30 days. Group E was administered 160 mg/kg A. indica leaf extract only for 30 days, after which it was stopped, and food and water were continued for another 30 days. All administrations were performed using means of oral gavage. On the 61st day, the animals were sacrificed, blood samples were collected for biochemical analysis, and the uterus excised for assessment [13].

Biochemical assays

Determination of total cholesterol content

This assay used a semi-automated chemistry analyzer (Mindray BA-88A Reagent system) with an AGAPPE test kit. Following the test kit’s instructions, the analyzer was programmed for the total cholesterol test. The blank microtube received only the cholesterol Biuret reagent (1000 μL). The standard tube was prepared by adding 10 μL of standard cholesterol solution and 1000 μL of the reagent, which was mixed. Sample tubes were prepared by adding 10 μL of sample A1 and 1000 μL of cholesterol reagent, which was also properly mixed in a tube labeled ‘A1’. The same procedure was followed for the remaining samples (A1-E5) in their respective tubes. All tubes were incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C. After incubation, the blank solution was aspirated into the flow cell to establish a baseline measurement in the analyzer. The standard solution and each sample were then measured to determine their absorbance, which was recorded [14].

Determination of total protein content

This assay used a semi-automated chemistry analyzer (Mindray BA-88A Reagent system) and the AGAPPE test kit. Following the test kit’s instructions, the analyzer was programmed for the total protein test. The blank microtube received only the protein Biuret reagent (1000 μL). The standard tube was prepared by adding 20 μL of standard total protein solution and 1000 μL of the reagent, which was properly mixed. Sample tubes were prepared by adding 20 μL of sample A1 and 1000 μL of total protein reagent which was also properly mixed. The same procedure was performed for the remaining samples (A1-E5) in their respective tubes. All tubes were incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C. After incubation, the blank solution was first aspirated into the flow cell to establish a baseline measurement in the analyzer. Then, the standard solution and each sample were measured individually to determine their absorbance, which was recorded for further analysis [6].

Determination of estradiol content

This assay used a microplate reader (Mindray MR-96A), microplate washer (Mindray MW-12A) and E2 Accubind “enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay” (ELISA) kit. Microplate wells for each sample, control, and reference material to compare were set up. A total of 25 μL of each sample was placed in the designated well. Fifty μL of estradiol biotin reagent was added to each well on the test plate. The plates were then gently swirled for 30 seconds and then incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. Next, 50 μL of estradiol enzyme reagent was added to all wells. The plate was then incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature. The contents of the plates were discarded, and the plates were dried with absorbent paper. The wells were washed thoroughly with 350 μL wash buffer solution and decanted thrice. Substrate solution (100 μL) was added to each well and incubated for 20 minutes, followed by a 50 μL of stop solution to halt the reaction. The light absorbed by the wells at 450 nm was measured within 15 minutes. Estradiol in the samples was determined using a dose-response curve [15].

Determination of progesterone content

Before proceeding with the assay, all reagents, serum reference calibrators, and controls were brought to room temperature (20-27 °C). Microplate wells were formatted for each calibrator, control, and specimen. The assay was performed in duplicate. A total of 0.025 mL of the appropriate serum reference calibrator, control, and specimen were pipetted into the assigned well. Then 0.05 mL of progesterone enzyme reagent was added to all wells. The microplate was swirled gently for 10-20 seconds to mix. 0.05 mL of progesterone biotin reagent was then added to all wells. The microplate was gently swirled for 10-20 seconds. The mixure was then covered and incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature. The content of the microplate was discarded by decantation, and the plate was also blotted dry with absorbent paper. A total of 0.35 mL of wash buffer was added to the plate. The plate was then decanted and the process repeated two additional times. Substrate reagent (0.1 mL) was then added to all wells, and care was taken not to shake the plate after the addition of the substrate. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes, after which 0.05 mL of stop solution was added to each well and gently mixed for 15-20 seconds. The absorbance was read for each well at 450 nm [15].

Histopathology analysis of organs

A 10% neutral buffered formalin solution was used to fix the tissue. The uterus was placed in appropriately labeled cassettes after being further dissected to choose the best area for inspection. Dehydration was performed using alcohol in an ascending sequence. Xylene was used for clearing, followed by paraffin wax infiltration. Tissues soaked in paraffin wax were then cut into ultra-thin sections of 5 microns using a semi-automated rotary microtome, allowed to dry overnight, and then, after being hydrated, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Dehydration with alcohol was repeated in ascending sequence. The sections were examined under a microscope and photographed after staining with dibutyl phthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX) [16].

HPLC procedure

HPLC analysis was performed at Bato Chemical Laboratory at the Lagos, Nigeria. The HPLC model was Shimadzu (Nexera MX). A special column called a C18 reverse phase column (ubondapak) was used for the separation, with dimensions of length: 100 mm, internal diameter: 4.6 mm, and thickness: 7 μm. A mixture of water and acetonitrile (70% acetonitrile, and 30% water) was used as the mobile phase to move the sample through the column. The HPLC device was connected to a ultraviolet (UV)–Vis diode array detector that uses ultraviolet (UV) light to analyze the chemicals (set at a specific wavelength of 254 nm). A pressure of 15 MPa was applied to push the samples through the column. First, standard solutions were injected into the machine. This resulted in a chromatogram showing peaks that represented the separated chemicals. Then 5 μL of the desired extract was injected into the HPLC system at a 2 mL/min constant flow rate. The device then produced another chromatogram with peaks for the chemicals in the extract. By comparing these peaks to the window set up earlier, the chemicals of interest present in the extract were identified [17].

Data analysis

GraphPad Prism software for Window, version 6.01 was used to create bar graphs showing the data. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze the data, followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the study.

Results

Acute toxicity test

During phase 1 acute toxicity test, no toxicity or mortality was observed at 10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, and 1000 mg/kg doses (Table 1).

In phase 2 testing, convincing evidence of toxicity and mortality was observed at 5000 mg/kg but no toxicity was observed at 1600 mg/kg and 2900 mg/kg, and no other signs of toxicity were observed; no secretions from the eyes, ear, nose, anus, or external genitalia, as well as no wasting, audible chattering, alopecia, or pallor in the eyes. The rats were not sluggish; they ate well and defecated normally. No ocular abnormalities, decreased motor activity, or neurological problems were observed.

Total serum cholesterol

The treatment of normal female rats with 400 mg/kg MSG resulted in a significant increase (32.73% [P≤0.05]) in plasma cholesterol levels in the preventive treatment. 80 and 160 mg/kg doses of the extract with MSG gave 29.35% and 14.81% increase, respectively (Figure 1).

Treatment with only 160 mg/kg extract resulted in a 71.04% increase in total plasma cholesterol. The curative study showed a 33% increase in cholesterol after induction with MSG for 30 days. A 1.56% and 31.17% increase in plasma cholesterol was observed when 80 and 160 mg/kg doses were administered, respectively, compared to the control (Figure 2).

Total protein content

No significant increase (P≥0.05) was observed in total plasma protein levels in normal female Wistar rats treated with 400 mg/kg MSG, both in the preventive and curative treatments (Figures 3 and 4).

When 80 mg/kg and 160 mg/kg doses of the extract were administered, they showed a 9.32% and 16.99% reduction in total plasma protein relative to the control (Figure 4). The 160 mg/kg extract alone did not significantly reduce the total plasma protein (4.66% [P≥0.05]).

Total serum estradiol

MSG treatment resulted in a 19.99% increase in estradiol levels. The 80 mg/kg and 160 mg/kg doses resulted in 16.92% and 32.41% reduction, respectively, relative to the control (Figure 5).

Total serum estradiol

MSG treatment resulted in a 19.99% increase in estradiol levels. The 80 mg/kg and 160 mg/kg doses resulted in 16.92% and 32.41% reduction, respectively, relative to the control (Figure 5).

The 160 mg/kg dose of the extract significantly reduced estradiol content compared to the control (63.4% [P≤0.01]). There was a 30.15% increase in estradiol levels in the curative treatment induced by MSG. A total of 80 mg/kg and 160 mg/kg doses resulted in 4.08% and 12.88% reduction, respectively, compared to the control (Figure 6).

A total of 160 mg/kg leaf extract dose resulted in a significant reduction (60.36% [P≤0.01]) in estradiol content.

Total serum progesterone

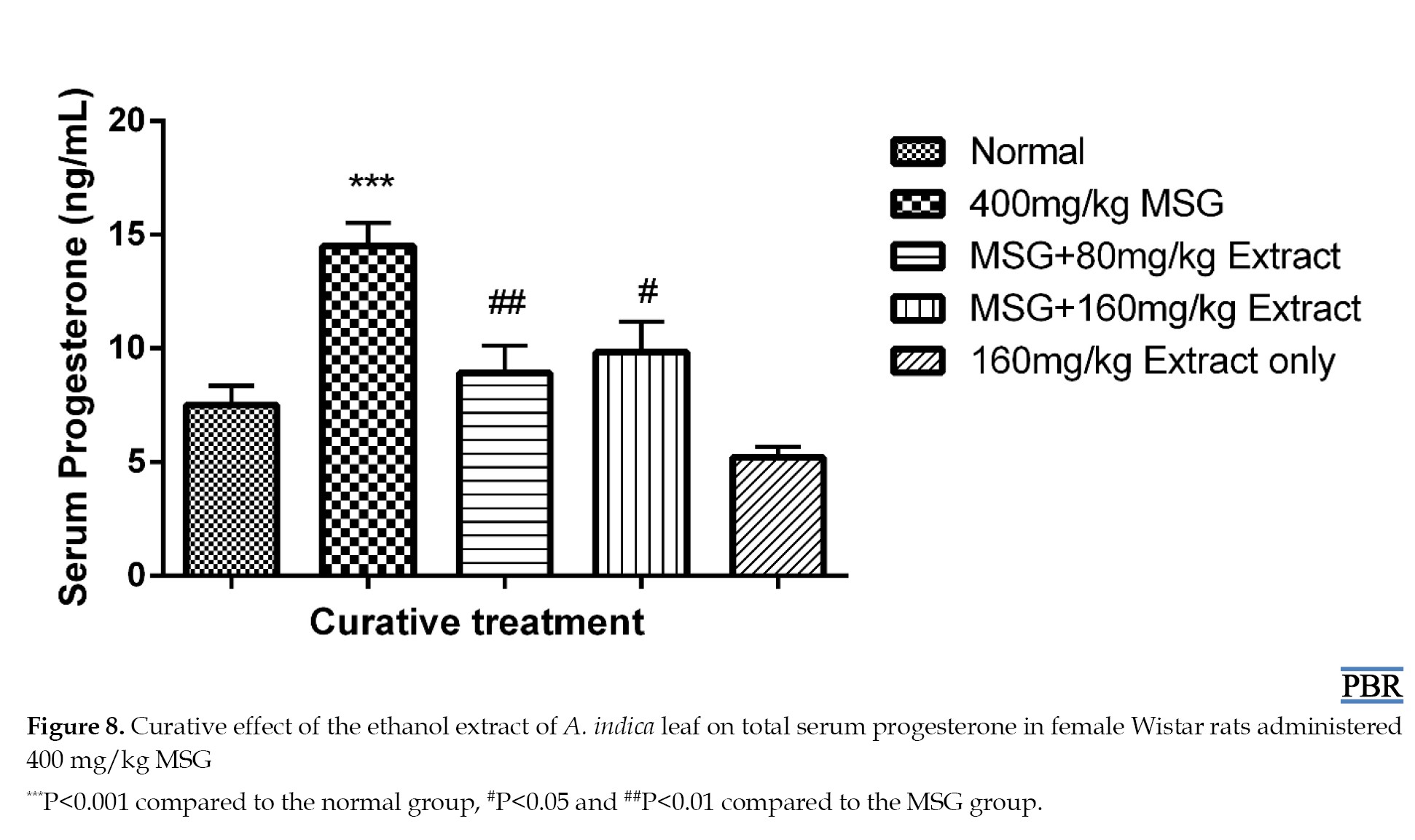

MSG treatment resulted in a significant elevation in progesterone levels, both in the preventive (104.15% P≤0.01) and curative (93.33% P≤0.001) treatments compared to the normal. Concurrent treatment with MSG and extract at both doses reduced the elevation of 51.95% and 34.39% in the preventive experiment (Figure 7), and 18.98% and 31.2% in the curative treatment (Figure 8).

Total serum progesterone

MSG treatment resulted in a significant elevation in progesterone levels, both in the preventive (104.15% P≤0.01) and curative (93.33% P≤0.001) treatments compared to the normal. Concurrent treatment with MSG and extract at both doses reduced the elevation of 51.95% and 34.39% in the preventive experiment (Figure 7), and 18.98% and 31.2% in the curative treatment (Figure 8).

A significant difference was observed with the extracts concerning the MSG group in the curative treatment (P≤0.01). Serum progesterone level in the 160 mg/kg extract only group was reduced by 30.67% compared to the normal.

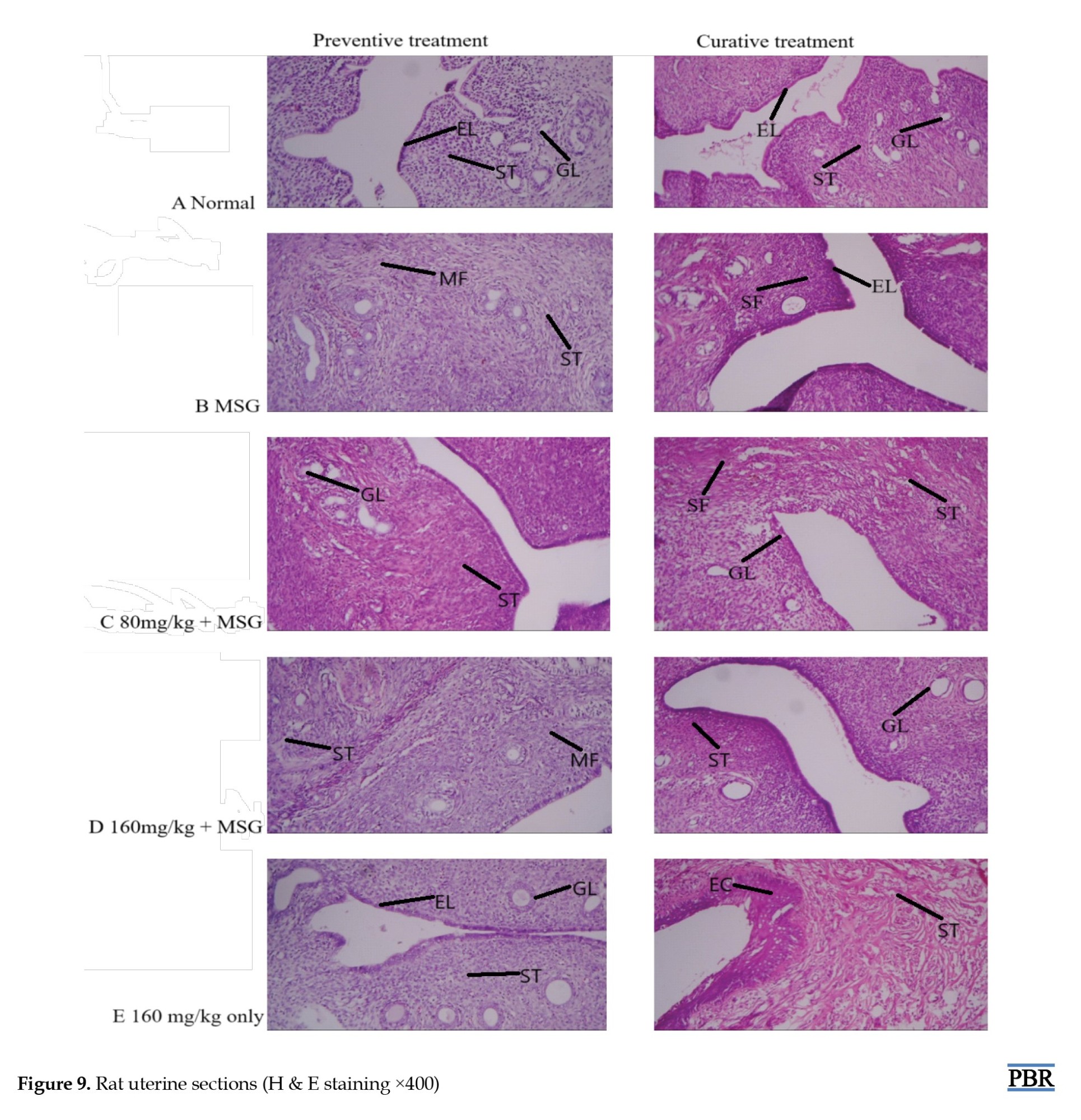

Histopathology result of the rat uterus

The normal uterus architecture (panel A) observed in the control group showed endometrial lining (EL), endometrial stroma (ST), and endometrial glands (GL) (Figure 9).

Histopathology result of the rat uterus

The normal uterus architecture (panel A) observed in the control group showed endometrial lining (EL), endometrial stroma (ST), and endometrial glands (GL) (Figure 9).

The MSG only group revealed spindle-shaped proliferating bundles of smooth muscle fibers (SF, MF), and collagenous ST characteristics of leiomyoma (panel B). In the group administered 80 mg/kg, endometrial GL surrounded by plump ST was observed in the preventive group (panel C). The curative treatment group also showed reduced spindle-shaped smooth muscle fibers (SF). The 160 mg/kg treated group (panel D) revealed mainly smooth muscle fibers (MF) supported by thick collagenous ST. A total of 160 mg/kg extract only group showed normal uterus architecture, EL, GL, endocrine (EC), and ST composed of fibrocollagenous connective tissue (panel E).

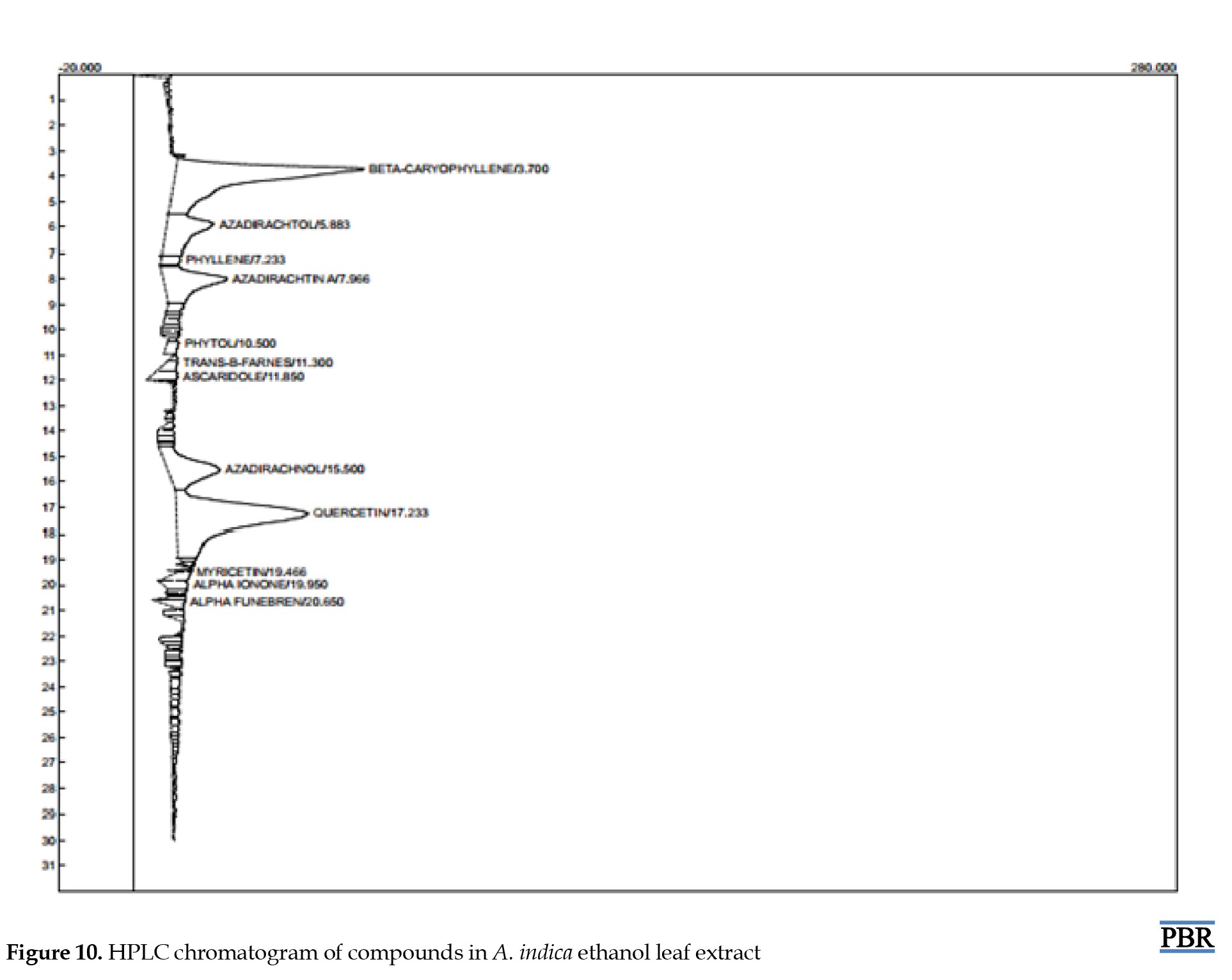

HPLC analysis result

HPLC analysis of ethanol leaf extract of A. indica revealed the presence of major components such as β-caryophyllin, azadirachnol, azadirachta-A, and quercetin, with decreased amounts of azadiractol, phyllene, myricetin, and phytol. Table 1 presents the various identified compounds, and Figure 10 shows the chromatogram.

HPLC analysis result

HPLC analysis of ethanol leaf extract of A. indica revealed the presence of major components such as β-caryophyllin, azadirachnol, azadirachta-A, and quercetin, with decreased amounts of azadiractol, phyllene, myricetin, and phytol. Table 1 presents the various identified compounds, and Figure 10 shows the chromatogram.

Discussion

The acute toxicity test results indicated that oral administration of A. indica leaf extract induced mortality in mice only at 5000 mg/kg, indicating that the plant extract is relatively safe at lower doses. No sedation, diarrhoea, change in gait, or body posture was observed at lower doses in the mice, and no decreased locomotory activity or hyperactivity was observed.

There was a considerable increase in cholesterol following the administration of MSG in both the curative and preventive tests. The extract demonstrated better ability to lower increased cholesterol levels in the curative experiment than in the preventive. The ability of the leaf extract to lower cholesterol may be due to a decrease in dephosphorylated 3-hydroxyl-3-methoxylglutamyl-CoA reductase (HMGR) levels, as well as an adverse effect on cholesterol production caused by the activation of glucagon and adrenaline [18]. Cholesterol is a crucial building block for the formation of many steroid hormones, which are powerful signaling molecules that control several processes in the body Elevatied serum cholesterol levels are typically linked to the activation of the enzyme HMGR, which catalyzes the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, the rate-limiting step of cholesterol synthesis [19].

The formation and development of uterine fibroids have been linked to ovarian steroid hormones, which have been shown to be crucial molecular indicators. Estradiol is unique in its ability to promote the growth of uterine cells because it binds to ERα receptors in the uterus and forms a complex that interacts with DNA in the nucleus to activate transcriptional promoters and enhancer regions that govern gene expression. This allows ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase II binding and the subsequent start of transcription, leading to protein production and increased uterine and ovarian cell proliferation [20].

Certain proteins linked to uterine fibroids have been shown to rise in response to MSG. This results from activating RNA polymerase and increasing its activity, activating transcriptional enhancer and promoter regions that control the production of genes linked to protein development [14]. In this study, there was no discernible difference between the MSG and treatment groups’ total protein content compared with the normal group. This is comparable to the results of previous studies [21].

In both curative and preventive trials, treatment with the ethanol extract of A. indica leaves lowered the increased estradiol levels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). Its effect on estradiol may be due to the inhibition of the enzyme aromatase, which is responsible for aromatizing testosterone and androstenedione to estrogens during the production of estradiol from cholesterol [15]. It may also contain phytochemicals that function as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, which, when stimulated continuously decrease, the expression or downregulate GnRH receptors on the anterior pituitary. Alternatively, it may be caused by an inducer of liver microsomal enzyme that increases estradiol metabolism [3]. As a result, less estradiol is generated.

Fibroids are caused by elevated protein, cholesterol, estrogen, and progesterone [3]. Experimental, clinical, and epidemiological data support the idea that ovarian steroid hormones play a role in the pathophysiology of uterine fibroids [22]. The higher progesterone levels were reduced dose-dependent after preventative treatment with A. indica leaf extract. Progesterone primarily affects fibroids via interacting with progesterone receptors, which are expressed more in leiomyomas than in normal myometrium [23]. Many studies have demonstrated that progesterone may play a significant role in interacting with growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins, even if the precise underlying processes that drive extracellular matrix deposition in uterine fibroids are still being investigated [24]. Progesterone has been demonstrated to be the primary mediator of the increase in transforming growth factor-β expression, which is one of the main growth agents that causes uterine fibroids to undergo fibrosis [25].

Saponins, steroids, terpenes, tannins, glycosides, alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, and oxalic acid are among the phytochemicals found in the plant [8]. The presence of these phytochemicals may explain the therapeutic efficacy. Activating the immune system and lowering cholesterol levels are saponins’ health advantages. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that saponin inhibits the aromatase enzyme [8], which is involved in estrogen synthesis. Studies have indicated that the plant has anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties that could be useful in treating fibroid [9]. These anti-proliferative properties may be linked to the presence of limonoids, which can limit cell growth and division. The anti-inflammatory qualities may alleviate the pain and inflammation associated with leiomyoma. Additionally, the antioxidant properties may protect against oxidative stress, which can lead to leiomyoma formation [26].

According to the HPLC analysis, the main compounds in the leaf extract of A. indica are beta-caryophyllene, azadirachtol, azadirachtin, azadirachnol, and quercetin (Table 1). These chemicals are implicated in the plant’s numerous medicinal advantages and could help manage uterine fibroids. It has been discovered that beta-caryophyllene is a sesquiterpene that is extensively found in the essential oils of many plants. Beta-caryophyllene is believed to contribute to numerous biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticarcinogenic properties [27]. Azadirachtin has antibacterial and antitumor properties, as well as the ability to reduce edema and encourage tissue healing [9]. Numerous investigations have demonstrated quercetin’s ability to have anticancer effects via various pathways, which have been validated in several in vitro and in vivo tumor models [27].

Conclusion

The levels of cholesterol, progesterone, and estradiol were lowered by the action of A. Indica leaves extract to varying degrees. Reduction of spindle-shaped fibers indicative of fibroid formation was seen at the lower dose of the extract. These results demonstrate the potential of the plant in managing fibroid.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin, Nigeria, authorized all protocols for utilizing animals in the experiment (Code: (EC/FP/023/04).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Rose Osarieme Imade and Buniyamin Adesina Ayinde; Experiments: Iyawe Osatohanmwen Andrex; Project administration: Charles Osemwegie Ogbemudia and Rose Osarieme Imade; Statistical analysis, investigation and writing: Rose Osarieme Imade; Review, editing, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Obasuyi and Queen Okoro of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital in Benin City for their contributions to the preparation of the histology slides and the analysis of the serum biochemical data. Gerald Eze of the Anatomy Department is also greatly appreciated for his help interpreting the histology slides.

References

- Chen HY, Lin PH, Shih YH, Wang KL, Hong YH, Shieh TM, et al. Natural antioxidant resveratrol suppresses uterine fibroid cell growth and extracellular matrix formation in vitro and in vivo. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019; 8(4):99.[DOI:10.3390/antiox8040099] [PMID]

- Farris M, Bastianelli C, Rosato E, Brosens I, Benagiano G. Uterine fibroids: An update on current and emerging medical treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019; 15:157-78. [DOI:10.2147/TCRM.S147318] [PMID]

- Koltsova AS, Pendina AA, Malysheva OV, Trusova ED, Staroverov DA, Yarmolinskaya MI, et al. In vitro effect of estrogen and progesterone on cytogenetic profile of uterine leiomyomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 26(1):96. [DOI:10.3390/ijms26010096] [PMID]

- Arip M, Yap VL, Rajagopal M, Selvaraja M, Dharmendra K, Chinnapan S. Evidence-based management of uterine fibroids with botanical drugs-A review. Front Pharmacol. 2022; 13:878407. [DOI:10.3389/fphar.2022.878407] [PMID]

- Liu JP, Yang H, Xia Y, Cardini F. Herbal preparations for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (2):CD005292. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005292.pub2] [PMID]

- Yashunina M. A study of the effect of an ethanolic extract of femitol on uterine fibroid in laboratory model. J Pharmacogn Nat Prod. 2021; 7:6. [Link]

- Innocent Ndubuisi Ezejiofor T, Henry Okoroafor C. Effects of ethanol extracts of Diodia sarmentosa leaves on biochemical and histopathological indices of monosodium glutamate-induced uterine leiomyoma in rats. Biomed Res Ther. 2022; 9(7):5140-8. [DOI:10.15419/bmrat.v9i7.749]

- Ujah II, Nsude CA, Ani ON, Alozieuwa UB, Okpako IO, Okwor AE. Phytochemicals of neem plant (Azadirachta indica) explains its use in traditional medicine and pest control. GSC Biol Pharm Sci. 2021; 14(2):165-71. [DOI:10.30574/gscbps.2021.14.2.0394]

- Su X, Liang Z, Xue Q, Liu J, Hao X, Wang C. A comprehensive review of azadirachtin: physicochemical properties, bioactivities, production, and biosynthesis. Acupunct Herb Med. 2023; 3:256-70. [DOI:10.1097/HM9.0000000000000086]

- Aworinde DO, Erinoso SM, Ibukunoluwa MR, Teniola SA. Herbal concoctions used in the management of some women-related health disorders in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria. J Appl Biosci. 2020; 147(1):15091-9. [Link]

- Alhassan HM, Haruna Yeldu M, Musa U, Adamu I, Marafa AH, Abdullahi H. Acute Toxicity and the Effects of Mangifera indica on Serum IL-6, and IFN-γ in Breast Cancer-Induced Albino Rats. Clin Oncol Res. 2021; 2021:1-6. [Link]

- Tepongning RN, Mbah JN, Avoulou FL, Jerme MM, Ndanga EK, Fekam FB. Hydroethanolic Extracts of Erigeron floribundus and Azadirachta indica Reduced Plasmodium berghei Parasitemia in Balb/c Mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018; 2018:5156710. [DOI:10.1155/2018/5156710] [PMID]

- Siti-Arffah K, Ridzuan PM, Nurkhaliesah M. Effect of some medicinal plants extract on monosodium glutamate induced uterine fibroid: A review. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2020; 7(11):490-5. [Link]

- Zakaria N, Mohd KS, Ahmed Saeed MA, Ahmed Hassan LE, Shafaei A, Al-Suede FSR, et al. Anti-Uterine fibroid effect of standardized labisia pumila var. alata extracts in vitro and in human uterine fibroid cancer xenograft model. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020; 21(4):943-51. [DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.4.943] [PMID]

- Lin Y, Yang C, Tang J, Li C, Zhang ZM, Xia BH, et al. Characterization and anti-uterine tumor effect of extract from Prunella vulgaris L. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020; 20(1):189. [DOI:10.1186/s12906-020-02986-5] [PMID]

- Brígido HPC, Varela ELP, Gomes ARQ, Bastos MLC, de Oliveira Feitosa A, do Rosário Marinho AM, et al. Evaluation of acute and subacute toxicity of ethanolic extract and fraction of alkaloids from bark of Aspidosperma nitidum in mice. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):18283. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-97637-1] [PMID]

- Tripathi IP, Mishra MK, Pardhi Y, Dwivedi A, Dwivedi N, Kamal A, et al. HPLC analysis of methanolic extract of some medicinal plant leaves of myrtaceae family. Int Pharm Sci. 2012; 2(3):49-53. [Link]

- Zakaria N, Mohd KS, Ali M, Saeed A, Ismail Z. cytotoxicity analysis against uterine fibroid cells preparation of standardized plant extracts. Biosci Res. 2018; 16(1):257-64.

- Bonazza C, Andrade SS, Sumikawa JT, Batista FP, Paredes-Gamero EJ, Girão MJ, et al. Primary Human Uterine Leiomyoma Cell Culture Quality Control: Some properties of myometrial cells cultured under serum deprivation conditions in the presence of ovarian steroids. PLoS One. 2016; 11(7):e0158578. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0158578] [PMID]

- Lin PH, Shih CK, Yen YT, Chiang W, Hsia SM. Adlay (Coix lachryma-jobi L. var. ma-yuen Stapf.) Hull Extract and Active Compounds Inhibit Proliferation of Primary Human Leiomyoma Cells and Protect against Sexual Hormone-Induced Mice Smooth Muscle Hyperproliferation. Molecules. 2019; 24(8):1556. [DOI:10.3390/molecules24081556] [PMID]

- Ahmed I, Ahmed N, Ahmed S, Ahmad F, Al-Subaie AM. Effect of emblica officinalis (Amla) on monosodium glutamate (MSG) induced uterine fibroids in wistar rats. Res J Pharm Technol 2020; 13(6):2535-9. [DOI:10.5958/0974-360X.2020.00451.5]

- Li ZL, Huang TY, Ho Y, Shih YJ, Chen YR, Tang HY, et al. Herbal medicine in uterine fibroid. In: Abduljabbar H, editor. Fibroids. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2021. [DOI:10.5772/intechopen.94101]

- Ali M, Ciebiera M, Vafaei S, Alkhrait S, Chen HY, Chiang YF, et al. Progesterone signaling and uterine fibroid pathogenesis; molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutics. Cells. 2023; 12(8):1117. [DOI:10.3390/cells12081117] [PMID]

- Donnez J. Uterine Fibroids and Progestogen Treatment: Lack of evidence of its efficacy: A review. J Clin Med. 2020; 9(12):3948. [DOI:10.3390/jcm9123948] [PMID]

- Koyejo OD, Rotimi OA, Abikpa EN, Bello OA, Rotimi SO. A review of the anti-fibroid potential of medicinal plants: Mechanisms and targeted signaling pathways. Trop J Nat Prod Res. 2021; 5(5):792-804. [DOI:10.26538/tjnpr/v5i5.1]

- AlAshqar A, Lulseged B, Mason-Otey A, Liang J, Begum UAM, Afrin S, et al. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Uterine Fibroids: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Antioxidants. 2023; 12(4):807. [DOI:10.3390/antiox12040807] [PMID]

- Szydłowska I, Nawrocka-Rutkowska J, Brodowska A, Marciniak A, Starczewski A, Szczuko M. Dietary natural compounds and vitamins as potential cofactors in uterine fibroids growth and development. Nutrients. 2022; 14(4):734. [DOI:10.3390/nu14040734] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Pharmacognosy

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |