Volume 11, Issue 3 (2025)

Pharm Biomed Res 2025, 11(3): 251-260 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amirzadeh M, Jabbarzadeh A, Ahmadi S, Ahmadi M, Ahmadi M. Structure-based In-silico Screening Reveals Promising Repurposed Drugs for Targeting Monkeypox Virus Proteins. Pharm Biomed Res 2025; 11 (3) :251-260

URL: http://pbr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-687-en.html

URL: http://pbr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-687-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Medicinal Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Institute for Cognitive Science Studies, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Infectious Disease, Faculty of Medicine, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Medicinal Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Institute for Cognitive Science Studies, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Infectious Disease, Faculty of Medicine, AJA University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1417 kb]

(154 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (367 Views)

Discussion

Most mpox-infected patients recovered without antiviral therapy, just for supportive care, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), lidocaine gel, and amitriptyline-based creams for painful lesions [25]. No specific antiviral against mpox is currently available. Three non-specific mpox antivirals are TPOXX (oral capsule, I.V. injectable vial), cidofovir (I.V. solution), and brincidofovir (oral tablets and suspensions). TPOXX inhibits VP37 protein and blocks its interaction with Rab9 GTPase and TIP47, preventing enveloped virions formation [26]. Cidofovir’s active form can inhibit viral DNA synthesis by inhibiting DNA polymerase 3’-5’ exonuclease activity, after two steps of phosphorylation [27]. Brincidofovir acts in the same mechanism as cidofovir, after hydrolysis of its hexadecyloxypropyl group. Although the FDA approves vaccinia immunoglobulin (VIGIV) for treating complications from vaccinia vaccination, the CDC permits using VIGIV to treat other orthopoxviruses during outbreaks. However, VIGIV has no proven benefit in treating mpox, and its efficacy against MPXV infection is unknown [28].

The side effects and less favorable pharmacokinetic profile of available antivirals can be addressed through nanodrug delivery. Nano drugs offer a wider therapeutic window and sustained release. Topical nano- and micro-antivirals have improved permeability. For example, in a study by Priyanka et al., the TPOXX gel formulation showed an enhanced cumulative permeation rate, which can be very effective on mpox lesions by facing viruses with a high concentration of this anti-orthopoxvirus drug [29]. Conjugating antiviral nanoparticles with target ligands can guide drugs to areas with high viral load. Lipophilic drug nanoparticles can be systemically administered due to altered properties [30].

Drug repurposing, or drug repositioning, aims to identify new therapeutic uses for existing drugs, including those already approved for a different indication. This approach can significantly reduce the time and cost of drug development as repurposed drugs have already been tested for safety and efficacy in humans during their initial approval [31]. Molecular docking is a computational technique that plays a crucial role in new drug discovery by predicting small molecules’ binding orientation and affinity to their target proteins.

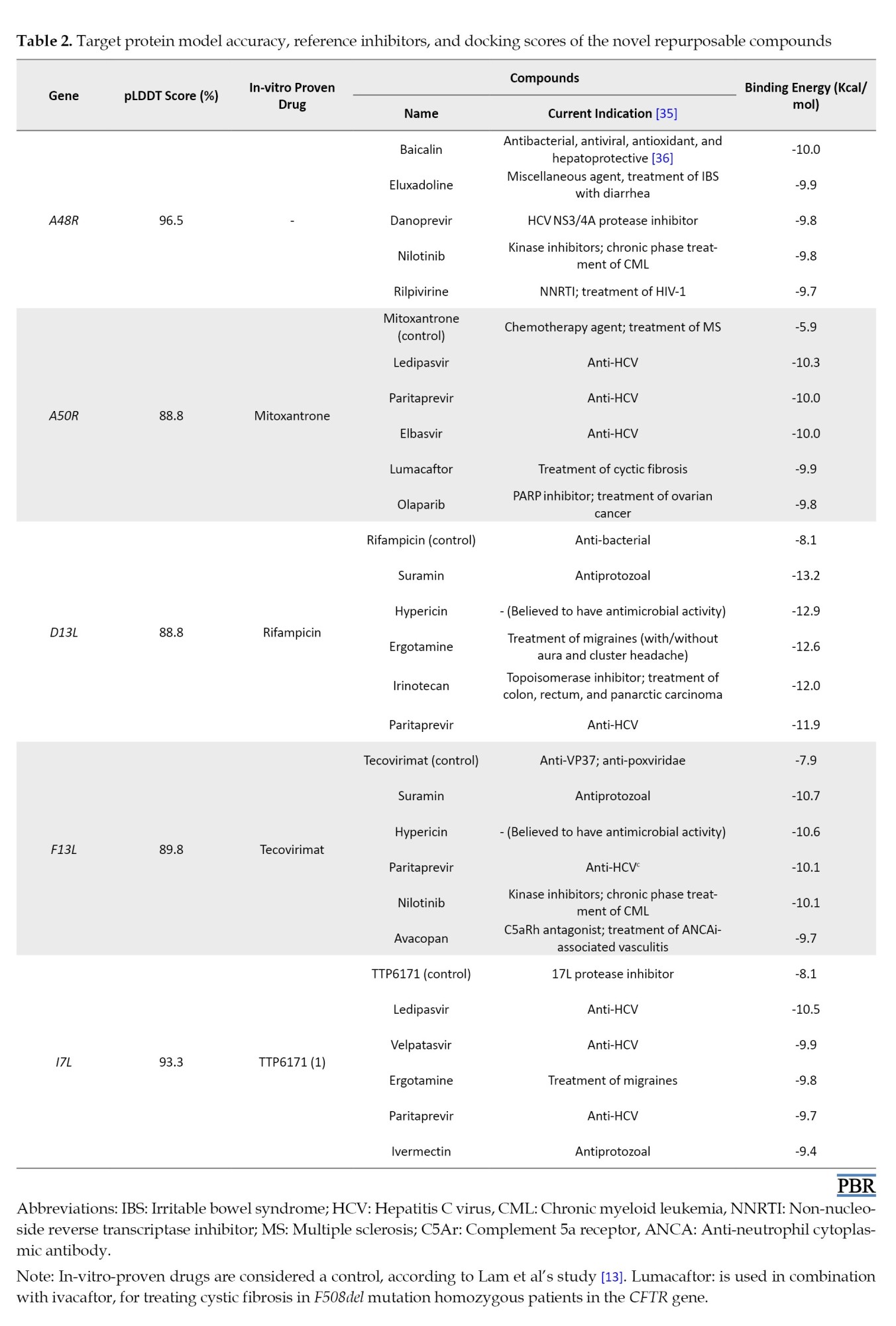

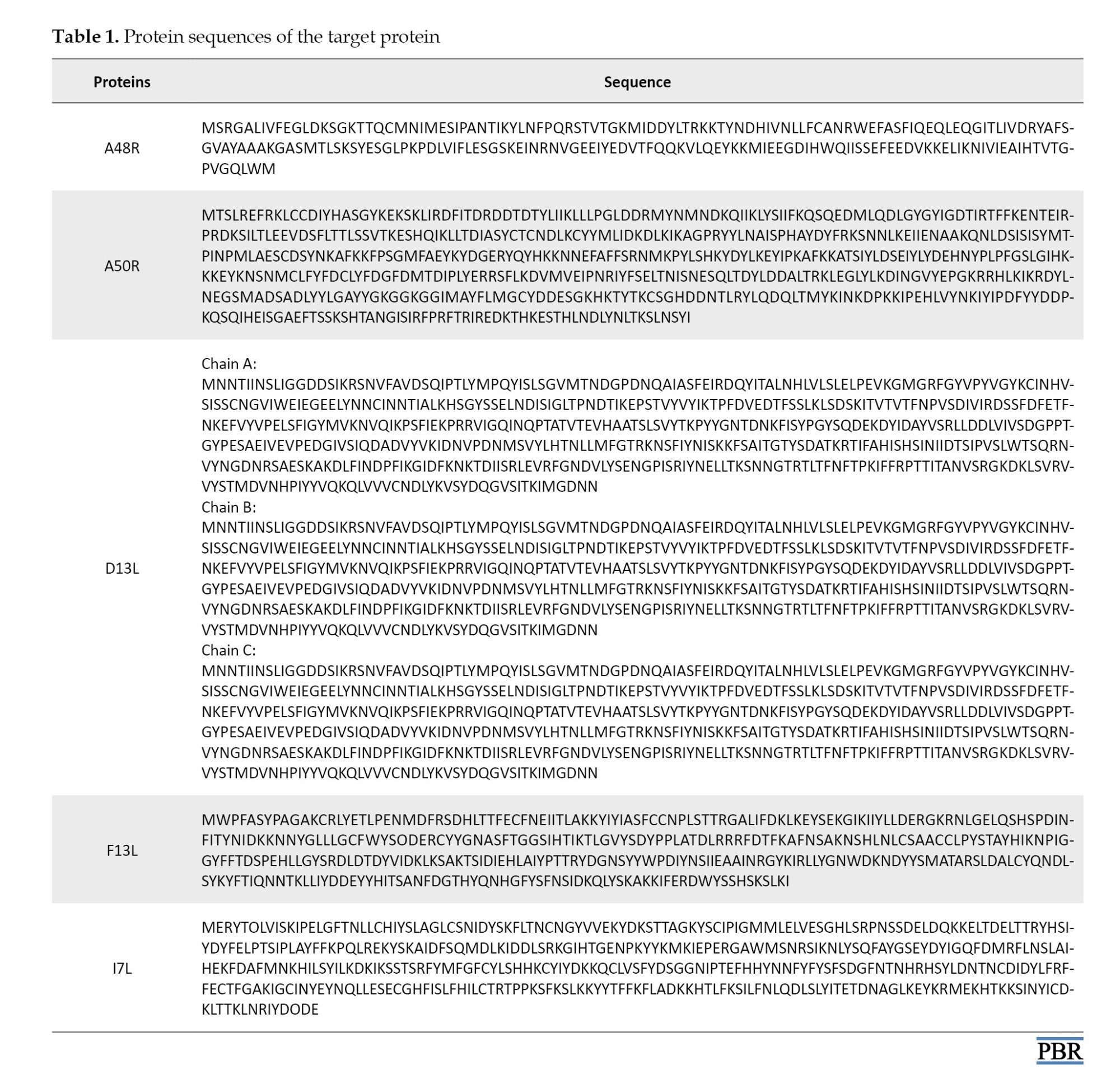

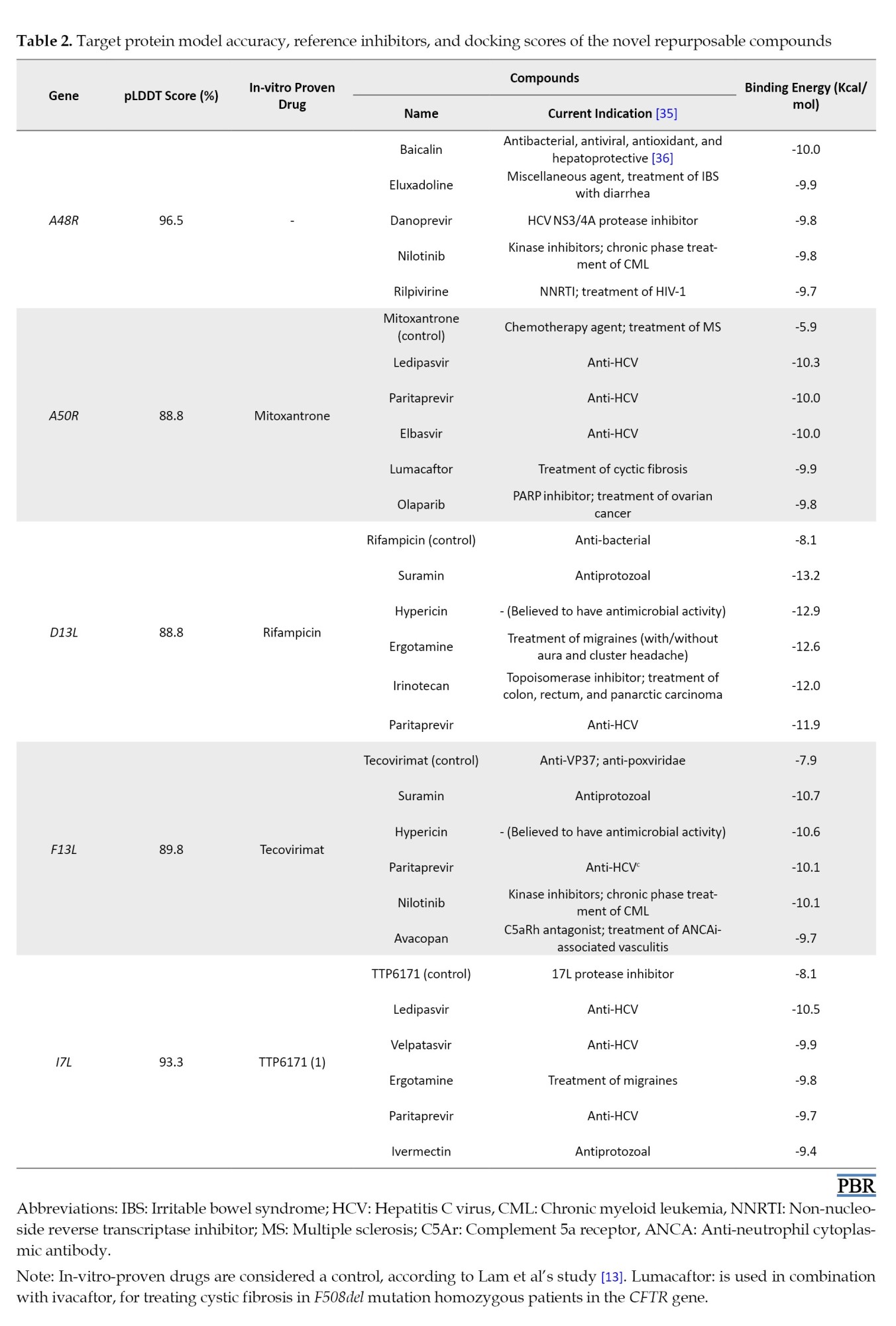

According to previous studies, we considered five viral proteins. A48R, which no drugs have targeted to date, is thymidylate kinase and is involved in the phosphorylation of thymidine and halogenated deoxyuridine monophosphate analogs. Lem et al. studied north-methanocarbathymidine (N-MCT) (a thymidine analog) and rutaecarpine (a cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitor), with bond energies of -7 and -9 Kcal/mol, respectively, as having the highest affinity to A48R [13]. MPXV DNA ligase (A50R), major capsid protein (D13L), envelope protein (F13L), and cysteine proteinase (17L) were also targeted in our study. A molecular docking study was conducted to evaluate the potential binding capability of the chosen compounds to the A48R, A50R, D13L, F13L, and I7L active sites. The results were compared with those of previously recognized protein inhibitors to determine whether the affinity of the newly repurposed compound was acceptable (Table 2).

Eventually, we selected the top 5 best compounds for each target. A48R was the only protein with no reference inhibitor. The selected compounds for A50R, ledipasvir, with an energy bond of -10.3 Kcal/mol, had a considerably higher affinity than mitoxantrone. Ledipasvir is a safe anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) with no contraindications, and it is usually used in combination with sofosbuvir [32, 33]. Suramin is an anti-trypanosomiasis agent with the highest affinity to D13L, with a docking score of -13.2 Kcal/mol. Suramin also shows a binding energy of -10.3 Kcal/mol to F13L, higher than the only approved anti-poxviridae drug, TPOXX. TTP-6171 is the only non-covalent 17L protease inhibitor reported in many papers [34]. Our study suggests that ledipasvir for 17L protease with higher affinity to the 17L protease than TTP-6171.

Conclusion

Infectious diseases are among the most challenging public health and macroeconomic issues. Frequent resistance has been reported in bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and viruses on the one hand. On the other hand, the mutations that occur in different pathogens, especially viruses, require health researchers to look for different antimicrobial drugs. Also, no effective antiviral treatment is available for many viral families, such as Flaviviridae (dengue virus, Zika virus, yellow fever virus, and Powassan virus), Filoviridae (Marburg virus), Paramyxoviridae (Nipah virus), and Togaviridae (chikungunya virus). Therefore, research in antiviral drug development can benefit this field. One of these viruses is the mpox virus, which African countries are experiencing new outbreaks of clade 1 of this DNA virus.

In this manuscript, we first made a general review of mpox infection. Then, we used molecular docking evaluation for each of the five mpox viral proteins. We evaluated five of the best compounds with higher affinity and pharmacological and pharmacokinetics properties, which are prone to side effects. We reported that our proposed first drug had a higher affinity for each protein than the current drugs targeting that protein. Our study can motivate researchers to investigate the paraclinical and clinical efficacy of the proposed drugs against the mpox virus in animal and human models.

Limitation

The ultimate efficacy of these proposed compounds will be outside of the in-silico atmosphere and requires further pharmacological and pharmacokinetic research to determine para-clinical and clinical efficacy and effective dosage. However, the significant advantage of drug repurposing is that the approval cost of them is significantly reduced by proving the safety profile of these drugs. Also, in this study, we used drugs reported to have antiviral efficacy in at least one in-silico, in-vitro, or in-vivo study. Therefore, only a limited number of ligands were used in this study. In addition, this study did not use other essential proteins in the virus, such as E9L, H5R, B1R, F10L, E8L, and A6R, which are known to play a crucial role in the virus’s replication and survival. Thus, more comprehensive studies are needed to obtain a complete list of effective drugs for all known viral proteins.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study did not involve any human participants or animal subjects. All experiments were conducted using computational and laboratory-based formulation methods only. Therefore, ethical approval and an institutional review board (IRB) code were not required for this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Shahed Ahmadi and Mousa Ahmadi; Data collection: Shahed Ahmadi, Mousa Ahmadi, and Mahdi Amirzadeh; Investigation: Shahed Ahmadi and Ali Jabbarzadeh; Writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, for its essential role in facilitating the molecular docking and visualization aspects of our in silico study on drug repurposing for the mpox virus.

Full-Text: (84 Views)

Introduction

The zoonotic infection of monkeypox (mpox) was the latest cause of declared public health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) in August 2024 [1]. Mpoxvirus (MPXV) is a double-stranded DNA virus in the viral family of poxviridae, subfamily of chordopoxvirinae, and orthopoxvirus genus. Many animals, such as African rodents (e.g. African pouched rats, squirrels, and dormice), mice, prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus), and non-human primates (e.g. chimpanzees, baboons (Papio cynocephalus), mangabeys, and jerboas), can hosts of mpox [2]. The reservoir host of this virus has not yet been identified.

Mpox infection presentations start with prodromal symptoms after an incubation period of 5-41 days [3]. The most prevalent manifestations, according to meta-analysis, are chills and fever, lymphadenopathy, lethargy, pruritus, myalgia, abdominal pain, pharyngitis, respiratory symptoms, nausea or vomiting, scrotal or penile edema, and conjunctivitis [4]. More than 85% of infected individuals in the 2022 outbreak showed skin lesions [4], mostly fluid-filled with high viral load, from whom the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) samples were taken to diagnose the virus [5]. Pregnant and breastfeeding females, younger than eight years old individuals, and any immunocompromised patients are at risk of severe infection [6, 7].

In many studies, three generations of smallpox vaccines have shown protection against mpox infections [8, 9]. ACAM2000, a second-generation vaccine based on Dryvax (first-generation), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in August 2024 for urgent use in the mpox outbreak [10]. The third-generation, modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic, a non-replicating, live, attenuated vaccine, was prequalified as the first vaccine against pox by the WHO on 13 September, 2024 and can be used in immunocompromised patients [11]. Tecovirimat (TPOXX), cidofovir, and brincidofovir are not specific medications against MPXV; however, they can be effective in preventing severe complications and mortality due to mpox infection [12]. New specific medications can play an essential role in decreasing the disease burden. Drug repurposing is one of the best methods for achieving this aim. Drug repurposing concerns discovering new indications for existing drugs, which is a quicker and often more economical method to find new treatments. Infectious diseases start by identifying potential targets, such as viral proteins or host factors critical for the pathogen’s life cycle. Molecular docking studies simulate the interaction between drugs and viral proteins and support prioritizing candidate drugs that may inhibit the key functions of viruses. In this study, by reviewing selected papers, we established five MPXV proteins: A48R (thymidylate kinase), A50R (DNA ligase), D13L (viral capsid protein), F13L (EEV formation protein), and 17L (protease), and evaluated existing drugs’ affinity to them.

Materials and Methods

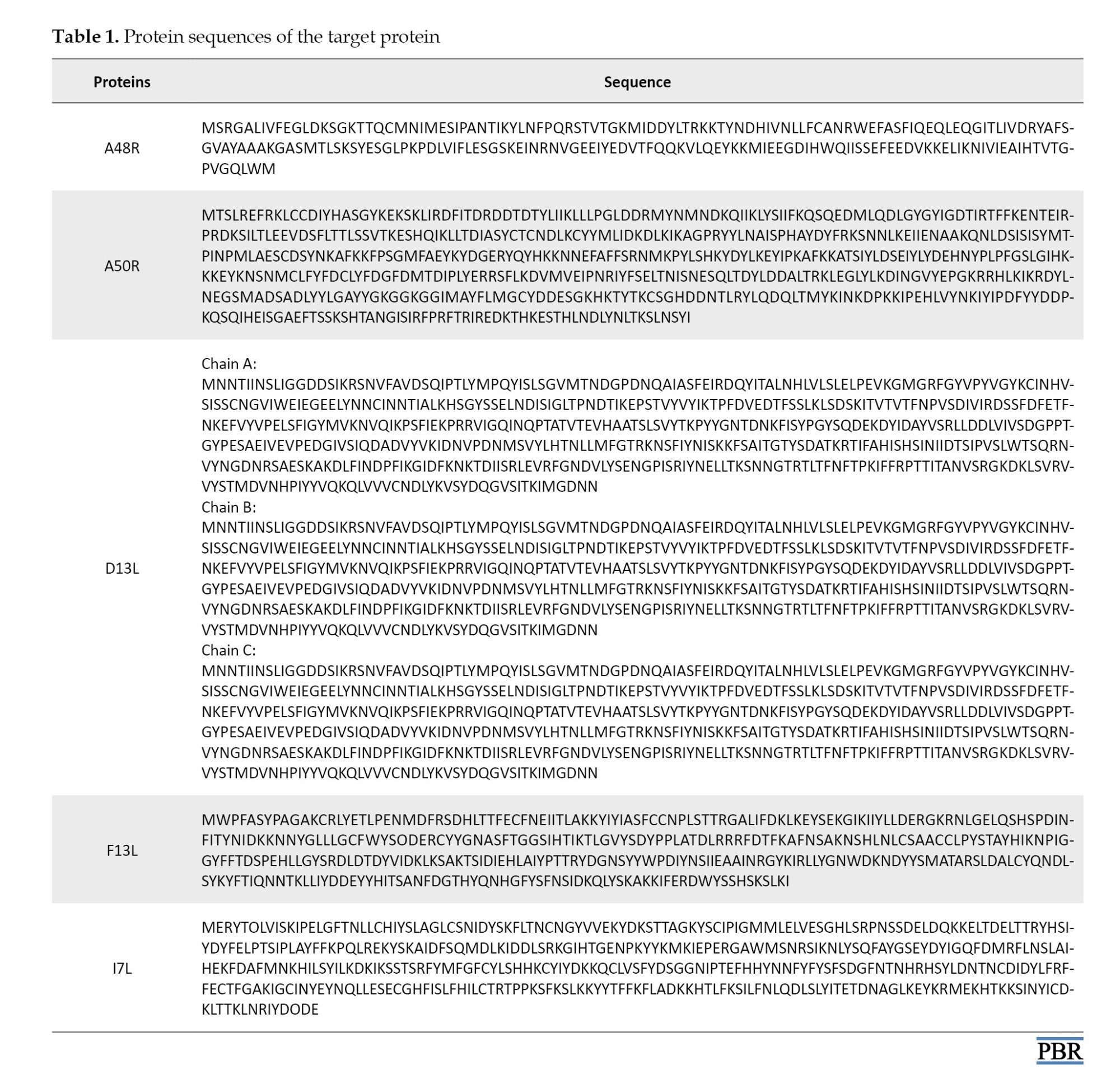

The protein sequences were obtained from a prior study by Lam et al. [13]. Using the AlphaFold2 Protein Structure Prediction Database via the ChimeraX 1.8 program, 3D structures of the proteins were modeled, and models with the highest per-residue accuracy of the structure (pLDDT) of 100 were chosen for docking analysis [14-16]. All proteins had high structural accuracy in their binding site. We further prepared the models using Chimera software, version 1.17.1 [17]. Hydrogen atoms and charges were added to the structures, and structure minimization was performed using the steepest descent steps and update interval set to 1000 and 100, respectively.

More than 300 ligands with previously proven antiviral properties were identified for the in-silico study against the mpox virus. The 3D structure of the ligands was downloaded from the PubChem database, in SDF format [18]. For compounds without an available 3D structure, the 3D structure was prepared by running an MM2 calculation on the 2D structure of the ligand using Chem3D Pro software [19].

This study used Autodock Vina within the PyRx software to determine the ligands’ affinity to target proteins [20, 21]. First, the protein structure was loaded into the software and then converted to PDBQT format. The ligand molecules were then loaded into the software, and further energy minimization and format change to PDBQT were performed. The binding site of the target proteins was identified based on the literature [13, 22]. The grid box center for A48R was (x,y,z: +5.5,-3.6,-5.9) and the diameter was (x,y,z: 26,26,26), center for A50R was (x,y,z: -14.4,-8.2,-13) and the diameter was (x,y,z: 26,25,26), center for D13L was (x,y,z: +16.7,+17,+14.2) and the diameter was (x,y,z: 37,37,37), center for F13L was (x,y,z: +6,+5.1,+3.4), and the diameter was (x,y,z: 31,29,31), center for I7L was (x,y,z: +6.3,+6.6,-18), and the diameter was (x,y,z: 33,41,37). Exhaustiveness was set to 8. The protein-ligand interactions in the docked structures were visualized and analyzed using PyMOL and Biovia Discovery Studio, which provided both 3D and 2D representations [23, 24] (Table 1).

Results

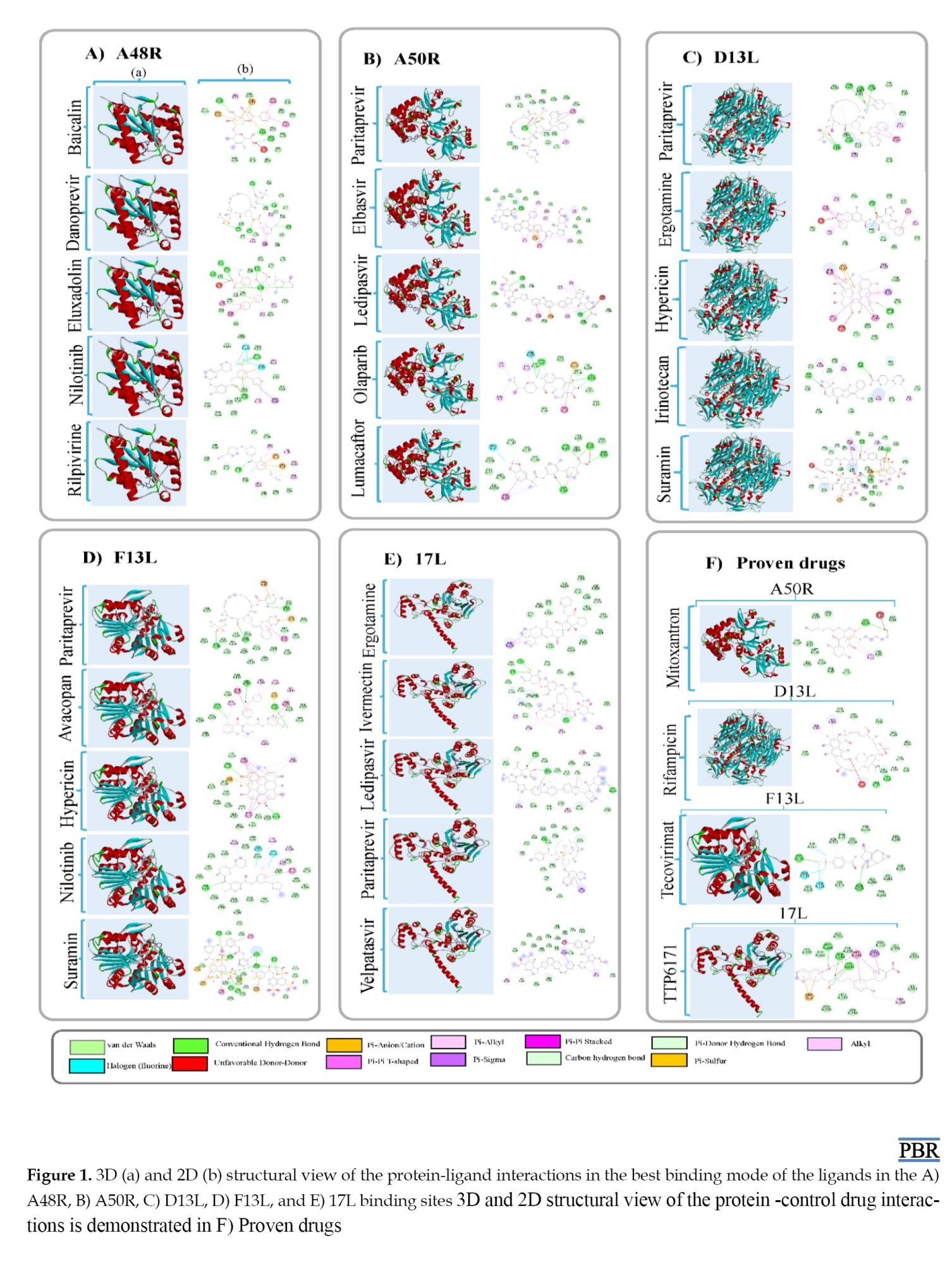

Molecular docking was conducted against five key Monkeypox virus (MPXV) proteins — A48R, A50R, D13L, F13L, and I7L — to identify high-affinity repurposed drug candidates. Binding energies and interaction profiles were evaluated using AutoDock Vina, PyMOL, and Discovery Studio, and compared with known reference inhibitors where available.

For A48R (thymidylate kinase), no clinically established inhibitor has been previously reported, making this target a novel therapeutic focus. Among all screened molecules, baicalin demonstrated the strongest binding affinity (−10.0 kcal/mol), forming multiple hydrogen bonds with key catalytic residues, including Lys18, Asp92, and Glu146 involved in nucleotide substrate recognition. Eluxadoline (−9.9 kcal/mol), danoprevir (−9.8 kcal/mol), nilotinib (−9.8 kcal/mol), and rilpivirine (−9.7 kcal/mol) also showed strong interactions, suggesting that compounds with flavonoid or antiviral scaffolds may competitively interfere with thymidine phosphorylation and disrupt viral nucleotide metabolism.

For A50R (DNA ligase), ledipasvir produced the highest binding affinity (−10.3 kcal/mol), markedly stronger than the reference inhibitor mitoxantrone (−5.9 kcal/mol). Ledipasvir interacted with residues Lys112, Glu224, and Tyr276 within the ATP-binding region, indicating possible inhibition of DNA strand-sealing. Other high-affinity molecules included paritaprevir (−10.0 kcal/mol), elbasvir (−10.0 kcal/mol), lumacaftor (−9.9 kcal/mol), and olaparib (−9.8 kcal/mol). These findings suggest that antiviral compounds originally developed for hepatitis C may inhibit MPXV ligase activity due to conserved enzymatic motifs.

For D13L (major capsid protein), suramin exhibited the greatest affinity (−13.2 kcal/mol), significantly surpassing rifampicin (−8.1 kcal/mol), a known control compound. Suramin formed extensive electrostatic and hydrogen-bond interactions with residues Arg235, Asp288, and Lys342 at the hexameric interface critical for capsid assembly. Hypericin (−12.9 kcal/mol), ergotamine (−12.6 kcal/mol), irinotecan (−12.0 kcal/mol), and paritaprevir (−11.9 kcal/mol) also showed robust binding patterns, implying potential disruption of viral particle formation and structural stability.

For F13L (envelope protein responsible for extracellular virion formation), suramin again demonstrated the strongest binding affinity (−10.7 kcal/mol), outperforming the FDA-approved anti-orthopoxvirus agent tecovirimat (−7.9 kcal/mol). Suramin formed hydrogen bonds with Ser250, Asp283, and Tyr305 within the phospholipase-like catalytic region involved in membrane wrapping and virion egress. Hypericin (−10.6 kcal/mol), paritaprevir (−10.1 kcal/mol), nilotinib (−10.1 kcal/mol), and avacopan (−9.7 kcal/mol) also bound favorably, indicating strong potential to inhibit extracellular enveloped virion maturation.

For I7L (cysteine protease), ledipasvir showed the highest affinity (−10.5 kcal/mol), exceeding the known inhibitor TTP-6171 (−8.1 kcal/mol). Ledipasvir interacted with catalytic residues Cys328 and His210 and exhibited π-π stacking with nearby aromatic residues, suggesting effective competitive inhibition. Velpatasvir (−9.9 kcal/mol), ergotamine (−9.8 kcal/mol), paritaprevir (−9.7 kcal/mol), and ivermectin (−9.4 kcal/mol) also demonstrated favorable binding. These results highlight that HCV NS5A-inhibitor classes may serve as potent MPXV protease inhibitors due to structural similarity within viral enzymatic pockets.

Collectively, suramin showed the strongest binding to structural proteins (D13L and F13L), while ledipasvir demonstrated the highest affinity toward enzymatic targets (A50R and I7L). Baicalin emerged as the top-performing natural compound against A48R. These findings indicate that a subset of clinically approved antiviral and anti-parasitic drugs exhibit strong binding to multiple MPXV targets, supporting their potential for rapid repurposing and further experimental validation (Figure 1).

The zoonotic infection of monkeypox (mpox) was the latest cause of declared public health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) in August 2024 [1]. Mpoxvirus (MPXV) is a double-stranded DNA virus in the viral family of poxviridae, subfamily of chordopoxvirinae, and orthopoxvirus genus. Many animals, such as African rodents (e.g. African pouched rats, squirrels, and dormice), mice, prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus), and non-human primates (e.g. chimpanzees, baboons (Papio cynocephalus), mangabeys, and jerboas), can hosts of mpox [2]. The reservoir host of this virus has not yet been identified.

Mpox infection presentations start with prodromal symptoms after an incubation period of 5-41 days [3]. The most prevalent manifestations, according to meta-analysis, are chills and fever, lymphadenopathy, lethargy, pruritus, myalgia, abdominal pain, pharyngitis, respiratory symptoms, nausea or vomiting, scrotal or penile edema, and conjunctivitis [4]. More than 85% of infected individuals in the 2022 outbreak showed skin lesions [4], mostly fluid-filled with high viral load, from whom the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) samples were taken to diagnose the virus [5]. Pregnant and breastfeeding females, younger than eight years old individuals, and any immunocompromised patients are at risk of severe infection [6, 7].

In many studies, three generations of smallpox vaccines have shown protection against mpox infections [8, 9]. ACAM2000, a second-generation vaccine based on Dryvax (first-generation), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in August 2024 for urgent use in the mpox outbreak [10]. The third-generation, modified vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic, a non-replicating, live, attenuated vaccine, was prequalified as the first vaccine against pox by the WHO on 13 September, 2024 and can be used in immunocompromised patients [11]. Tecovirimat (TPOXX), cidofovir, and brincidofovir are not specific medications against MPXV; however, they can be effective in preventing severe complications and mortality due to mpox infection [12]. New specific medications can play an essential role in decreasing the disease burden. Drug repurposing is one of the best methods for achieving this aim. Drug repurposing concerns discovering new indications for existing drugs, which is a quicker and often more economical method to find new treatments. Infectious diseases start by identifying potential targets, such as viral proteins or host factors critical for the pathogen’s life cycle. Molecular docking studies simulate the interaction between drugs and viral proteins and support prioritizing candidate drugs that may inhibit the key functions of viruses. In this study, by reviewing selected papers, we established five MPXV proteins: A48R (thymidylate kinase), A50R (DNA ligase), D13L (viral capsid protein), F13L (EEV formation protein), and 17L (protease), and evaluated existing drugs’ affinity to them.

Materials and Methods

The protein sequences were obtained from a prior study by Lam et al. [13]. Using the AlphaFold2 Protein Structure Prediction Database via the ChimeraX 1.8 program, 3D structures of the proteins were modeled, and models with the highest per-residue accuracy of the structure (pLDDT) of 100 were chosen for docking analysis [14-16]. All proteins had high structural accuracy in their binding site. We further prepared the models using Chimera software, version 1.17.1 [17]. Hydrogen atoms and charges were added to the structures, and structure minimization was performed using the steepest descent steps and update interval set to 1000 and 100, respectively.

More than 300 ligands with previously proven antiviral properties were identified for the in-silico study against the mpox virus. The 3D structure of the ligands was downloaded from the PubChem database, in SDF format [18]. For compounds without an available 3D structure, the 3D structure was prepared by running an MM2 calculation on the 2D structure of the ligand using Chem3D Pro software [19].

This study used Autodock Vina within the PyRx software to determine the ligands’ affinity to target proteins [20, 21]. First, the protein structure was loaded into the software and then converted to PDBQT format. The ligand molecules were then loaded into the software, and further energy minimization and format change to PDBQT were performed. The binding site of the target proteins was identified based on the literature [13, 22]. The grid box center for A48R was (x,y,z: +5.5,-3.6,-5.9) and the diameter was (x,y,z: 26,26,26), center for A50R was (x,y,z: -14.4,-8.2,-13) and the diameter was (x,y,z: 26,25,26), center for D13L was (x,y,z: +16.7,+17,+14.2) and the diameter was (x,y,z: 37,37,37), center for F13L was (x,y,z: +6,+5.1,+3.4), and the diameter was (x,y,z: 31,29,31), center for I7L was (x,y,z: +6.3,+6.6,-18), and the diameter was (x,y,z: 33,41,37). Exhaustiveness was set to 8. The protein-ligand interactions in the docked structures were visualized and analyzed using PyMOL and Biovia Discovery Studio, which provided both 3D and 2D representations [23, 24] (Table 1).

Results

Molecular docking was conducted against five key Monkeypox virus (MPXV) proteins — A48R, A50R, D13L, F13L, and I7L — to identify high-affinity repurposed drug candidates. Binding energies and interaction profiles were evaluated using AutoDock Vina, PyMOL, and Discovery Studio, and compared with known reference inhibitors where available.

For A48R (thymidylate kinase), no clinically established inhibitor has been previously reported, making this target a novel therapeutic focus. Among all screened molecules, baicalin demonstrated the strongest binding affinity (−10.0 kcal/mol), forming multiple hydrogen bonds with key catalytic residues, including Lys18, Asp92, and Glu146 involved in nucleotide substrate recognition. Eluxadoline (−9.9 kcal/mol), danoprevir (−9.8 kcal/mol), nilotinib (−9.8 kcal/mol), and rilpivirine (−9.7 kcal/mol) also showed strong interactions, suggesting that compounds with flavonoid or antiviral scaffolds may competitively interfere with thymidine phosphorylation and disrupt viral nucleotide metabolism.

For A50R (DNA ligase), ledipasvir produced the highest binding affinity (−10.3 kcal/mol), markedly stronger than the reference inhibitor mitoxantrone (−5.9 kcal/mol). Ledipasvir interacted with residues Lys112, Glu224, and Tyr276 within the ATP-binding region, indicating possible inhibition of DNA strand-sealing. Other high-affinity molecules included paritaprevir (−10.0 kcal/mol), elbasvir (−10.0 kcal/mol), lumacaftor (−9.9 kcal/mol), and olaparib (−9.8 kcal/mol). These findings suggest that antiviral compounds originally developed for hepatitis C may inhibit MPXV ligase activity due to conserved enzymatic motifs.

For D13L (major capsid protein), suramin exhibited the greatest affinity (−13.2 kcal/mol), significantly surpassing rifampicin (−8.1 kcal/mol), a known control compound. Suramin formed extensive electrostatic and hydrogen-bond interactions with residues Arg235, Asp288, and Lys342 at the hexameric interface critical for capsid assembly. Hypericin (−12.9 kcal/mol), ergotamine (−12.6 kcal/mol), irinotecan (−12.0 kcal/mol), and paritaprevir (−11.9 kcal/mol) also showed robust binding patterns, implying potential disruption of viral particle formation and structural stability.

For F13L (envelope protein responsible for extracellular virion formation), suramin again demonstrated the strongest binding affinity (−10.7 kcal/mol), outperforming the FDA-approved anti-orthopoxvirus agent tecovirimat (−7.9 kcal/mol). Suramin formed hydrogen bonds with Ser250, Asp283, and Tyr305 within the phospholipase-like catalytic region involved in membrane wrapping and virion egress. Hypericin (−10.6 kcal/mol), paritaprevir (−10.1 kcal/mol), nilotinib (−10.1 kcal/mol), and avacopan (−9.7 kcal/mol) also bound favorably, indicating strong potential to inhibit extracellular enveloped virion maturation.

For I7L (cysteine protease), ledipasvir showed the highest affinity (−10.5 kcal/mol), exceeding the known inhibitor TTP-6171 (−8.1 kcal/mol). Ledipasvir interacted with catalytic residues Cys328 and His210 and exhibited π-π stacking with nearby aromatic residues, suggesting effective competitive inhibition. Velpatasvir (−9.9 kcal/mol), ergotamine (−9.8 kcal/mol), paritaprevir (−9.7 kcal/mol), and ivermectin (−9.4 kcal/mol) also demonstrated favorable binding. These results highlight that HCV NS5A-inhibitor classes may serve as potent MPXV protease inhibitors due to structural similarity within viral enzymatic pockets.

Collectively, suramin showed the strongest binding to structural proteins (D13L and F13L), while ledipasvir demonstrated the highest affinity toward enzymatic targets (A50R and I7L). Baicalin emerged as the top-performing natural compound against A48R. These findings indicate that a subset of clinically approved antiviral and anti-parasitic drugs exhibit strong binding to multiple MPXV targets, supporting their potential for rapid repurposing and further experimental validation (Figure 1).

Discussion

Most mpox-infected patients recovered without antiviral therapy, just for supportive care, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), lidocaine gel, and amitriptyline-based creams for painful lesions [25]. No specific antiviral against mpox is currently available. Three non-specific mpox antivirals are TPOXX (oral capsule, I.V. injectable vial), cidofovir (I.V. solution), and brincidofovir (oral tablets and suspensions). TPOXX inhibits VP37 protein and blocks its interaction with Rab9 GTPase and TIP47, preventing enveloped virions formation [26]. Cidofovir’s active form can inhibit viral DNA synthesis by inhibiting DNA polymerase 3’-5’ exonuclease activity, after two steps of phosphorylation [27]. Brincidofovir acts in the same mechanism as cidofovir, after hydrolysis of its hexadecyloxypropyl group. Although the FDA approves vaccinia immunoglobulin (VIGIV) for treating complications from vaccinia vaccination, the CDC permits using VIGIV to treat other orthopoxviruses during outbreaks. However, VIGIV has no proven benefit in treating mpox, and its efficacy against MPXV infection is unknown [28].

The side effects and less favorable pharmacokinetic profile of available antivirals can be addressed through nanodrug delivery. Nano drugs offer a wider therapeutic window and sustained release. Topical nano- and micro-antivirals have improved permeability. For example, in a study by Priyanka et al., the TPOXX gel formulation showed an enhanced cumulative permeation rate, which can be very effective on mpox lesions by facing viruses with a high concentration of this anti-orthopoxvirus drug [29]. Conjugating antiviral nanoparticles with target ligands can guide drugs to areas with high viral load. Lipophilic drug nanoparticles can be systemically administered due to altered properties [30].

Drug repurposing, or drug repositioning, aims to identify new therapeutic uses for existing drugs, including those already approved for a different indication. This approach can significantly reduce the time and cost of drug development as repurposed drugs have already been tested for safety and efficacy in humans during their initial approval [31]. Molecular docking is a computational technique that plays a crucial role in new drug discovery by predicting small molecules’ binding orientation and affinity to their target proteins.

According to previous studies, we considered five viral proteins. A48R, which no drugs have targeted to date, is thymidylate kinase and is involved in the phosphorylation of thymidine and halogenated deoxyuridine monophosphate analogs. Lem et al. studied north-methanocarbathymidine (N-MCT) (a thymidine analog) and rutaecarpine (a cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitor), with bond energies of -7 and -9 Kcal/mol, respectively, as having the highest affinity to A48R [13]. MPXV DNA ligase (A50R), major capsid protein (D13L), envelope protein (F13L), and cysteine proteinase (17L) were also targeted in our study. A molecular docking study was conducted to evaluate the potential binding capability of the chosen compounds to the A48R, A50R, D13L, F13L, and I7L active sites. The results were compared with those of previously recognized protein inhibitors to determine whether the affinity of the newly repurposed compound was acceptable (Table 2).

Eventually, we selected the top 5 best compounds for each target. A48R was the only protein with no reference inhibitor. The selected compounds for A50R, ledipasvir, with an energy bond of -10.3 Kcal/mol, had a considerably higher affinity than mitoxantrone. Ledipasvir is a safe anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) with no contraindications, and it is usually used in combination with sofosbuvir [32, 33]. Suramin is an anti-trypanosomiasis agent with the highest affinity to D13L, with a docking score of -13.2 Kcal/mol. Suramin also shows a binding energy of -10.3 Kcal/mol to F13L, higher than the only approved anti-poxviridae drug, TPOXX. TTP-6171 is the only non-covalent 17L protease inhibitor reported in many papers [34]. Our study suggests that ledipasvir for 17L protease with higher affinity to the 17L protease than TTP-6171.

Conclusion

Infectious diseases are among the most challenging public health and macroeconomic issues. Frequent resistance has been reported in bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and viruses on the one hand. On the other hand, the mutations that occur in different pathogens, especially viruses, require health researchers to look for different antimicrobial drugs. Also, no effective antiviral treatment is available for many viral families, such as Flaviviridae (dengue virus, Zika virus, yellow fever virus, and Powassan virus), Filoviridae (Marburg virus), Paramyxoviridae (Nipah virus), and Togaviridae (chikungunya virus). Therefore, research in antiviral drug development can benefit this field. One of these viruses is the mpox virus, which African countries are experiencing new outbreaks of clade 1 of this DNA virus.

In this manuscript, we first made a general review of mpox infection. Then, we used molecular docking evaluation for each of the five mpox viral proteins. We evaluated five of the best compounds with higher affinity and pharmacological and pharmacokinetics properties, which are prone to side effects. We reported that our proposed first drug had a higher affinity for each protein than the current drugs targeting that protein. Our study can motivate researchers to investigate the paraclinical and clinical efficacy of the proposed drugs against the mpox virus in animal and human models.

Limitation

The ultimate efficacy of these proposed compounds will be outside of the in-silico atmosphere and requires further pharmacological and pharmacokinetic research to determine para-clinical and clinical efficacy and effective dosage. However, the significant advantage of drug repurposing is that the approval cost of them is significantly reduced by proving the safety profile of these drugs. Also, in this study, we used drugs reported to have antiviral efficacy in at least one in-silico, in-vitro, or in-vivo study. Therefore, only a limited number of ligands were used in this study. In addition, this study did not use other essential proteins in the virus, such as E9L, H5R, B1R, F10L, E8L, and A6R, which are known to play a crucial role in the virus’s replication and survival. Thus, more comprehensive studies are needed to obtain a complete list of effective drugs for all known viral proteins.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study did not involve any human participants or animal subjects. All experiments were conducted using computational and laboratory-based formulation methods only. Therefore, ethical approval and an institutional review board (IRB) code were not required for this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Shahed Ahmadi and Mousa Ahmadi; Data collection: Shahed Ahmadi, Mousa Ahmadi, and Mahdi Amirzadeh; Investigation: Shahed Ahmadi and Ali Jabbarzadeh; Writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, for its essential role in facilitating the molecular docking and visualization aspects of our in silico study on drug repurposing for the mpox virus.

References

- WHO. WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [Link]

- Li K, Yuan Y, Jiang L, Liu Y, Liu Y, Zhang L. Animal host range of mpox virus. J Med Virol. 2023; 95(2):e28513. [DOI:10.1002/jmv.28513] [PMID]

- Naseer MM, Afzal M, Fatima T, Nabiha, Rafique H, Munir A. Human monkeypox virus: A review on the globally emerging virus. Biomed Lett. 2024; 10(1):26-41. [DOI:10.47262/BL/10.1.20242161]

- Yon H, Shin H, Shin JI, Shin JU, Shin YH, Lee J, et al. Clinical manifestations of human monkeypox infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2023; 33(4):e2446. [DOI:10.1002/rmv.2446] [PMID]

- Correia C, Alpalhão M, de Sousa D, Vieitez-Frade J, Pelerito A, Cordeiro R, et al. Detection of mpox using polymerase chain reaction from the skin and oropharynx over the course of infection: A prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023; 89(4):822-3.[DOI:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.05.071] [PMID]

- Rao AK, Schrodt CA, Minhaj FS, Waltenburg MA, Cash-Goldwasser S, Yu Y, et al. Interim clinical treatment considerations for severe manifestations of mpox-United States, February 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023; 72(9):232-43. [DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm7209a4] [PMID]

- WHO. Clinical management and infection prevention and control guideline. Geneva 2025. [Link]

- Edghill-Smith Y, Golding H, Manischewitz J, King LR, Scott D, Bray M, et al. Smallpox vaccine-induced antibodies are necessary and sufficient for protection against monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2005; 11(7):740-7. [DOI:10.1038/nm1261] [PMID]

- Earl PL, Americo JL, Wyatt LS, Eller LA, Whitbeck JC, Cohen GH, et al. Immunogenicity of a highly attenuated MVA smallpox vaccine and protection against monkeypox. Nature. 2004; 428(6979):182-5. [DOI:10.1038/nature02331] [PMID]

- FDA. FDA Roundup: August 30, 2024. Maryland: FDA; 2024. [Link]

- WHO. WHO prequalifies the first vaccine against mpox. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [Link]

- Russo AT, Grosenbach DW, Brasel TL, Baker RO, Cawthon AG, Reynolds E, et al. Effects of treatment delay on efficacy of tecovirimat following lethal aerosol monkeypox virus challenge in cynomolgus macaques. J Infect Dis. 2018; 218(9):1490-9. [DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiy326] [PMID]

- Lam HYI, Guan JS, Mu Y. In silico repurposed drugs against monkeypox virus. Molecules. 2022; 27(16):5277. [DOI:10.3390/molecules27165277] [PMID]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021; 596(7873):583-9. [DOI:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2] [PMID]

- Meng EC, Goddard TD, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Pearson ZJ, Morris JH, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023; 32(11):e4792.[DOI:10.1002/pro.4792] [PMID]

- Mirdita M, Schütze K, Moriwaki Y, Heo L, Ovchinnikov S, Steinegger M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods. 2022; 19(6):679-82. [DOI:10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1] [PMID]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004; 25(13):1605-12. [DOI:10.1002/jcc.20084] [PMID]

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51(D1):D1373-80. [DOI:10.1093/nar/gkac956] [PMID]

- Hinchliffe A. CS Chem3D Pro 3.5 and CS MOPAC Pro (Mac and Windows) UK. New Jersey: Wiley; 1997. [DOI:10.1002/ejtc.54]

- Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021; 61(8):3891-8. [DOI:10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203] [PMID]

- Dallakyan S, Olson AJ. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol. 2015; 1263:243-50. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19] [PMID]

- Lokhande KB, Shrivastava A, Singh A. In silico discovery of potent inhibitors against monkeypox’s major structural proteins. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023; 41(23):14259-74. [DOI:10.1080/07391102.2023.2183342] [PMID]

- Schrödinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System.Version. 2015; 1:8. [Link]

- BIOVIA, Dassault systèmes. Discovery studio visualizer v21.1.0.20298. San Diego: Dassault Systèmes Biovia Corp; 2021. [Link]

- Maredia H, Sartori-Valinotti JC, Ranganath N, Tosh PK, O’Horo JC, Shah AS. Supportive care management recommendations for mucocutaneous manifestations of monkeypox infection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023; 98(6):828-32.[DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.01.019] [PMID]

- Mucker EM, Goff AJ, Shamblin JD, Grosenbach DW, Damon IK, Mehal JM, et al. Efficacy of tecovirimat (ST-246) in nonhuman primates infected with variola virus (Smallpox). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013; 57(12):6246-53. [DOI:10.1128/AAC.00977-13] [PMID]

- Magee WC, Hostetler KY, Evans DH. Mechanism of inhibition of vaccinia virus DNA polymerase by cidofovir diphosphate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005; 49(8):3153-62. [DOI:10.1128/AAC.49.8.3153-3162.2005] [PMID]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mpox treatment information for healthcare professionals.: Atlanta: CDC; 2023. [Link]

- Priyanka NS, Neeraja P, Mangilal T, Kumar MR. Formulation and evaluation of gel loaded with microspheres of apremilast for transdermal delivery system. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2019; 12(2):411-7. [DOI:10.22159/ajpcr.2019.v12i2.29374]

- Zhou J, Krishnan N, Jiang Y, Fang RH, Zhang L. Nanotechnology for virus treatment. Nano Today. 2021; 36:101031.[DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101031] [PMID]

- Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA, Escott KJ, Hopper S, Wells A, et al. Drug repurposing: Progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019; 18(1):41-58. [DOI:10.1038/nrd.2018.168] [PMID]

- Alarfaj SJ, Alzahrani A, Alotaibi A, Almutairi M, Hakami M, Alhomaid N, et al. The effectiveness and safety of direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus treatment: A single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2022; 30(10):1448-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2022.07.005] [PMID]

- Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Rossaro L, Bernstein DE, Lawitz E, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370(20):1879-88. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1402355] [PMID]

- Dodaro A, Pavan M, Moro S. Targeting the I7L Protease: A rational design for Anti-Monkeypox Drugs? Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(8):7119. [DOI:10.3390/ijms24087119] [PMID]

- DrugBank. Open Data Drug & Drug Target Database (version 5.1.12) [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 9 November 2025]. Available from: [Link]

- Hu Z, Guan Y, Hu W, Xu Z, Ishfaq M. An overview of pharmacological activities of baicalin and its aglycone baicalein: New insights into molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2022; 25(1):14-26. [DOI:10.22038/IJBMS.2022.60380.13381] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Research |

Subject:

Medical Chemistry

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |